Albany, where I live, is on the banks of Princess Royal Harbour, one of the great natural harbours in the Southern Hemisphere. This little historical town with its Mediterranean climate and a population of around 37,000 is the centre for the Great Southern Region of Western Australia.

The Great Southern Region with a population of about 60,000 stretches 200 km along the magnificent south coast of Western Australia and for about the same distance inland.

Everywhere in the so-called Developed World homelessness is increasing — people are roaming the streets with nowhere to live — and the Great Southern Region and Albany Town are no different to the rest of the world.

In May 2018, here in Camelot, it was estimated that at least 200 people were homeless, maybe 300 .

It was reported that they were living in the sand dunes and anywhere where it was dry and in winter, warm. Men women and children were living in cars and couch surfing and where they could find somewhere, they would squat.

Those disturbing numbers were revealed in a ‘Feasibility Study’, commissioned by a number of businesses and organisations in Albany and the region, together with the Town of Albany and the Great Southern Development Commission, the regional arm of the West Australian Government.

The aim of the study was to ‘investigate developing crisis accommodation for the at risk population in the Great Southern Region.’

The report was excellent. It detailed the challenges the community faced in helping the homeless in the Great Southern Region. It identified a number of realistic and achievable answers. The problem was then and still is, funding. There is no money.

Therefore, surprise, surprise, nothing has really changed in the 3 years since that report was written, if anything the homeless numbers have increased, as they have all around Western Australia.

The crisis centres in the region are still full and inadequate. Some don’t have the money to stay open all year round.

Why is it in our privileged world we can find millions even billions to provide sports facilities for everyone, many of which are only used once or twice a week, yet we struggle to find the money to put a roof over the heads, to provide shelter and warmth for the homeless, for the destitute?

The temperature as I write is 12.5C and there were hailstones 10cm deep in Albany this morning after a night of thunder, lightning and torrential rain. There is snow on the nearby Stirling Range — what the hell it must have been like trying to sleep rough or in a car last night, I cannot imagine. Probably hell.

Governments are always claiming they don’t have the money for this and for that except if it is for something that will attract votes. The homeless will never elect a government but that is no excuse to ignore study after study that show there are big savings available to government if only they would address the challenge of housing the homeless and not, cynically, have their eyes on the next election. This is one study:

In the 12 months after the 44 clients in this Perth-based study were housed, emergency admissions were reduced by 57% and overnight stays by 53%. The overall health-care saving was A$404,028.

Here’s another – note this is after housing was provided:

Even after deducting the cost of housing, a 2011 Australian study of 268 participants found savings of $2,182 per person after 12 months.

There have been so many of these studies, all have the same result. There is a return on investment when the homeless are housed which is as good or better than any investment governments may make and that is just the dollars. The improvement in the condition, the return on the human capital is immeasurable.

So why don’t governments, both state and federal do something positive about the national shame of homelessness? We have a federal government which has just brought down a budget that has put the country into debt for decades, all designed they tell us, to provide funds so that Australia can recover from the Covid19 pandemic and build an infrastructure and a labour force for the future –a future, that, obviously, doesn’t include caring for the homeless.

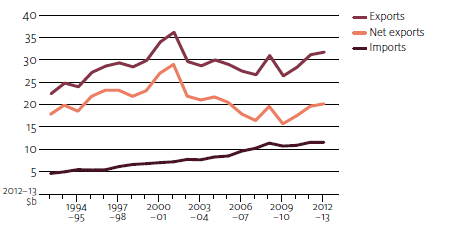

The Government of Western Australia is rolling in money as the price of iron ore sky rockets and other minerals, like gold, not far behind. Thirty per cent of the gross income of the WA Government is currently derived from royalties from the minerals being dug up and exported. So the question is why can’t some of this windfall go into homes for the 10,000 who are homeless in Western Australia?

The Story Gets Worse.

In addition to the hundreds of people who are homeless there is a social housing waitlist in the Great Southern of 500, most of whom are in Albany. There are 15,700 families on the social housing waitlist in Western Australia, some 30,000 to 40,000 people.

That means that between 1,000 and 1,500 people in the Great Southern are paying rents which they cannot afford and are therefore in the awful predicament of ‘rent stress’.

Social or Community Housing is for those on low to moderate income and for those with a disability. There is an international standard which states that if anyone is paying more than 30% of their household income in rent then they are deemed to be under ‘financial or rent stress’.

Experience, not just in Albany, but around the world shows that when there is ‘rent stress’ the first item to be cut from the budget is food. Just ask Foodbank, ask the Salvos and the Vinnies about the demands on their services to provide for those, who after paying all their bills, have no money left for food.

In the UK they have recognised this problem and free school lunches are provided for all children in grades 1 and 2, and to others where there is a social need. What a great idea and I’ll bet there are kids in Albany who wouldn’t mind a good feed at lunch time. What a caring way to ensure that our precious children grow to their potential during those early years and of course, don’t eat cheap junk food.

In the UK they have recognised this problem and free school lunches are provided for all children in grades 1 and 2, and to others where there is a social need. What a great idea and I’ll bet there are kids in Albany who wouldn’t mind a good feed at lunch time. What a caring way to ensure that our precious children grow to their potential during those early years and of course, don’t eat cheap junk food.

There is another factor in Albany that digs into the family budget and that is the lack of public transport and like everywhere, the lowest rents are those farthest away from the CBD, so having a car is a must and paying for it can be a problem and another drain on the family budget. That’s why so many turn up at Foodbank driving a car, it’s a necessity.

Our rural towns are shrinking, shops are boarded up the banks have gone and as the farms get bigger, big machinery with self steer and satellite navigation is replacing people. Increasingly people who have spent many years living and working on farms are now migrating to the regional centres. The majority are at the time of life when retraining is necessary and difficult, so it takes them time to settle into a new life.

Our rural towns are shrinking, shops are boarded up the banks have gone and as the farms get bigger, big machinery with self steer and satellite navigation is replacing people. Increasingly people who have spent many years living and working on farms are now migrating to the regional centres. The majority are at the time of life when retraining is necessary and difficult, so it takes them time to settle into a new life.

There is no safety net for these people many of whom only have their furniture, a car and their superannuation available to them, the latter many years away, so they have no option but to accept a period of low wages as they retrain. Unable to fund a mortgage the only option is to rent, which invariably means ‘rent stress’.

As house prices escalate all over the country and rents increase, they are forecast to increase by another 20% in WA in the next 12 months, more and more people, people vital to the functioning of society and through no fault of their own are finding there is nowhere to rent and when there is, the rent will put them also into ‘rent stress’.

A few years ago there was a report from the UK discussing the need for social houses for ‘key workers’ in the London area found that ‘key workers’ like nurses, police, council employees (garbage collectors, parks and garden workers etc), bus drivers (3000 vacancies) and the like, could no longer afford the rents that were being demanded.

Job vacancy rates were becoming an embarrassment for councils especially when they couldn’t put enough police on the beat, enough nurses into the hospitals and care homes and when the garbage was being left in the streets.

Some key workers had tried moving to the outer fringes of south east London where rents were lower, only to find the costs to get to work and the time it took on public transport negated what they saved on rent, it became too hard and they quit and moved to a cheaper area.

‘Anthony Scantlebury from the GMB London Ambulance Service comments on a typical emergency workers daily routine:

“If you finish at 7pm in the evening, before you get home and get yourself sorted out, it is probably 10 o’clock at night. And then you need to leave home at half past four in the morning again to start work at seven.”

He continued “that cuts down on your sleep time and you get progressively more tired as the week goes on.”

Additionally, Ken Marsh, the chairman of metropolitan police federation has noted that whilst the very nature of policing has always been challenging, stress levels are the highest they have ever been, with the average shift being 10.5 hours. If one takes into consideration the commute of the officer from outside of London, this can lead to a 14-hour day.’

When I read the article I thought, that is London and their high prices, prices far in excess of prices in Australia and particularly in Perth – so it will never happen here.

How wrong I was, the same challenge is now emerging not only in the big cities in Australia where the median house price is over $1 million and out of reach for nurses and police on $60,000 to $70,000 a year, but the problem is now spreading to some regional towns like Albany, where the median house price is $500,000. There are houses in the $400,000 to $450,000 range however the mortgage on those houses over 20 years and with a $20,000 deposit incurs monthly repayments of about $1,700 which is more expensive than the cost of renting in the Great Southern at about $1,450 a month.

We Know the Extent of the Problem.

On the 27th and 28th of March 2021 Anglicare Western Australia (WA) took a Snapshot to capture the number of properties suitable for people on low income. The results were disturbing to say the least. It found that the total number of rental properties throughout Western Australia on that weekend was 3,695, just half the number that were available on the same weekend in 2020. For the South West it was down by 30%. The housing market boomed and landlords it seems, sold their investments, perhaps to help with the cost of the pandemic?

For those landlords left in the market the laws of supply and demand came into play and in spite of inflation and wage growth being at almost zero, the rates in the metro area increased by 16% from $370 to $430 per week, in the South West and Great Southern the increase was 12% from $330 to $370 and in the North West the rates had increased by 17% pushing the weekly rent to between $470 and $550.

That weekend in Western Australia:

- Only 1% of rental properties in the state were available for rent. So 36 properties.

- 98% of the properties available were not affordable to those on a minimum wage. Really none especially for the young.

- 15,700 households were on the waitlist in Western Australia (around 30,000 people)

- 8000 people were living in temporary accommodation, couch surfing, squatting, living in cars

- 1000+ people were sleeping rough

What is Being Done to Meet the Need?

The story is a bad one for the State where the Premier has been known to claim WA is keeping Australia afloat with the boom in mining. In a State where nearly 30% of its gross income comes from mining royalties the lack of social conscience in a Labor government is breathtaking and and runs against the ethos of the party of the working man and woman. This is the record of the WA Government:

- Over the last three years the number of social housing properties in Western Australia has declined by 1155.

- Only 119 social housing properties were built in the last 3 years compared to 956 in 2016-17

- For the period 2017-2020, the West Australian government delivered 224 new social housing homes, but sold off 726 social homes.

If those numbers seem a bit confusing it is because there are others in the business of providing social housing as well as the State Government and logically enough they are referred to as Community Housing Providers (CHPs) who are all not for profit companies.

Community Housing Providers.

In the main Community Housing Providers or CHPs, not for profit companies, in each state, do two things:

- They manage a portfolio of properties for the State Government.

- They build their own properties for rent under the same terms and conditions as the properties they manage for the government.

In the commercial rental market landlords only provide accommodation for rent when they can show an acceptable return on their investment. They can also increase the rent on the property when demand is strong, like now and they can, theoretically, reduce the rent to meet an oversupplied market.

The same conditions do not apply to CHPs because they can only charge between 25% and 30% of the household income for rent. Only those with a low to moderate household incomes qualify for a CHP property, so, the CHP knows to within reasonable limits, what income it will derive from every property.

It also knows again within reasonable limits, what it will cost for each property in annual repairs and maintenance.

There are no concessions in the building industry for CHPs. CHPs pay commercial rates for land and they pay the same amount as any developer or builder to have houses built on that land.

What the CHP cannot do is charge a rent, comparable to the market rate which means that the CHP is denied a rate of return comparable to commercial rates, which in turn inhibits their ability to make a profit and put that money to build more houses to meet the ever increasing demands from the most vulnerable people in our community.

Research has shown and has been confirmed by CHPs new housing budgets, that it is difficult for them to grow and provide homes to meet the ever growing need, without some help from government.

The West Australian Government has shown over the last few years that it isn’t really interested in providing homes for those who need them.

These statistics demand to be repeated again and again.

The state waitlist stands at nearly 18,000. Over the last 3 years the number of social houses in Western Australia has declined by 1,155. Just 119 social housing properties were built in the last three years, compared with 956 in 2016/17 and over the last five years a total of 945 social housing properties were sold off. There has been a net loss of 502 properties which means the government of WA has sold more properties than it has built.

Where to From Here?

It is evident from their recent performance that the West Australian Government doesn’t have social housing as a major item on their budget. It is also plain as day, that the Federal Government don’t know anything about the subject so they care even less. In the billions of dollars in the federal budget not one shekel has been allocated to one of the biggest challenges facing Australia today and that is housing the homeless and the needy.

Why is it that our normally rapacious governments don’t have any appetite to find homes for the homeless and those under rent stress, when the financial gain to them is substantial and proven? Do they not want the pressure on the health service reduced? Do they not want more money to put into medical research, or aged care?

Money is as cheap now as it will ever be, CHPs are in a good position to borrow, to build to meet the needs of our most disadvantaged, what these not for profit organisations need is some understanding and some help not only from governments but from society in general, from philanthropists in particular, no matter how big or small, to help them build a solid foundation to build more houses well into the future. The problem is only getting bigger and it will not go away without a huge effort from every sector of society.

Money is as cheap now as it will ever be, CHPs are in a good position to borrow, to build to meet the needs of our most disadvantaged, what these not for profit organisations need is some understanding and some help not only from governments but from society in general, from philanthropists in particular, no matter how big or small, to help them build a solid foundation to build more houses well into the future. The problem is only getting bigger and it will not go away without a huge effort from every sector of society.

There is a great story in the Bible of the Good Samaritan. A man was beaten by robbers and left for dead. A priest came by and passed on the other side, so to did a Levite, but a Samaritan crossed the road and gave aid to the man, put him on his donkey, cared for him at an inn and when he left he gave the innkeeper money to take care of the man and said that if more was spent then he would pay it on his return.

I am not an outwardly religious person, but I have remembered that story because it is all about care, care for neighbours, treating neighbours like you would want to be treated. It is time that pressure was put on our governments by the voters of this land to take care of our neighbours, those who deserve a roof over their heads and enough money to pay for food.

Think about it tonight when you have dinner and then later go to a warm and clean bed.

Note: I am a director of a Community Housing Provider. The views expressed here I mine and mine alone and not necessarily those of the CHP.