The Changing of the Guard.

Preamble.

Over recent times as Australian agriculture has endured droughts, poor prices and incompetent governments; amid the chaos there have been two major overriding topics for discussion.

The first has been trying to separate the rumours, the gossip and the chit chat from the truth regarding the extent, the size of Chinese investment in Australian agriculture, in land, as distinct from agribusiness or food processing.

There is a body of opinion that claims Chinese interests, including Sovereign Funds have made substantial purchases of land in Australia, using a variety of investment vehicles, which have enabled them to avoid scrutiny by the Foreign Investment Review Board (FIRB).

We have the figures from the FIRB and we name who the biggest investors in Australia agriculture have been over recent times and the results will surprise you. China is at the bottom of the list, below Hong Kong. So why the public and in some cases political interest in China who ‘officially’ appear to be a minor investor? Is it xenophobia, fear, nationalism? — they all mean the same thing really. Do we fear China and is that because we don’t understand them? Whose fault is that?

These are difficult questions for us as a people and as an industry. It is a far more serious question for the media, and I believe the media should shoulder a great deal of the blame, because they have wrung every bit of emotion they can out of China and Chinese investment in Australia, giving voice to rumour and innuendo. Yet the records show that the media have been at least less than diligent and probably lazy in failing to report who the big, billion dollar plus, non-Chinese investors have been in Australian agricultural land over recent years.

The second big question is, forgetting agriculture, can we now manage, as a country, without China? We have all but exported our manufacturing base, everything from engineering, to clothing to hardware to food processing — you name it, what we once made ourselves we now get from China.

If it’s ‘Made in China’ it’s designed to be affordable. The more we buy from China the more dependent we become on them and the more vulnerable we are as the alternatives become uncompetitive.

The resource boom of the last last decade should have made Australia strong but there’s a fly in the ointment, Barclay’s Bank Kieran Davies reports that Australian household debt is equal to 130% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) this compares to an average of 78% average across the advanced world making us more vulnerable than most to another financial crisis.

So we’ve spent the boom on paying ourselves wages and salaries big enough to build the biggest houses in the world with ‘entertainment centres’ and a bathroom for every resident, double garages to hold the boat and the dual cab 4wd ‘trucks’. Enough left over to holidays to exotic destinations and the like — instead of spending our money on our country, on the infrastructure future generations will need to make us world competitive.

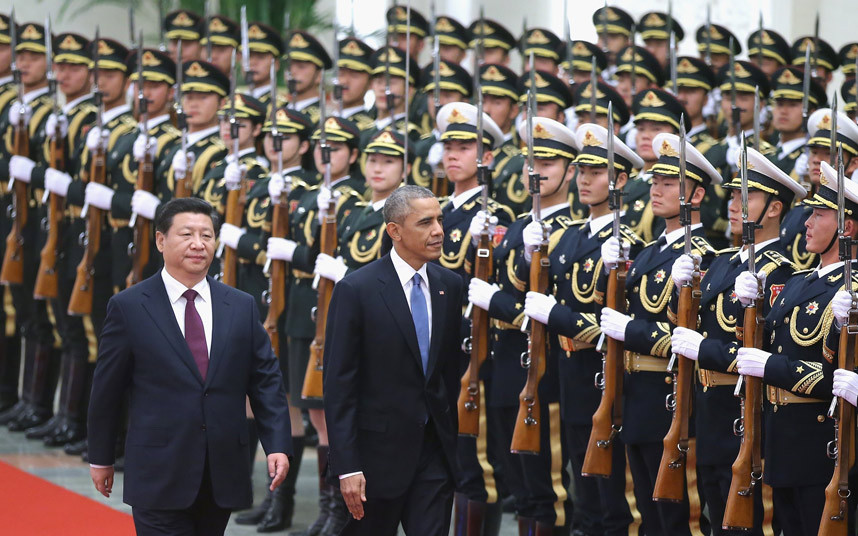

China is now the world’s largest economy. America will fight them for that position — but no matter what happens, China’s influence on the Australia will continue to grow.

Australia’s challenge will be to find the point of balance in our relationship between our greatest ally, America, and the country we cannot manage without — China.