It’s a frightening proposition but just look at the evidence.

In 1968, Paul Ehrlich in his book ‘Population Bomb’ made the prediction the world faced massive starvation due to overpopulation. He wrote:

The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.

Then along came Dr Norman Borlaug, ‘the father of the Green Revolution’, and his team of plant breeders and the world was saved from starvation. In 1970, Borlaug became a Nobel Laureate.

Between 1950 and 2004 world wheat yields rose from an average of 750kg/ha to 2750kg/ha (FAO), due to the worldwide adoption of high yielding, high input short straw wheat varieties, developed by Borlaug and his teams. Similar improvements were achieved in the yields of maize and rice.

This revolution in plant breeding, combined with new chemicals to control pests and diseases averted the global starvation tragedy predicted by Ehrlich.

In the last forty years the population of the world has doubled and, by and large they have all been fed.

The millions, who have died of starvation over that period, didn’t die because there wasn’t any food for them; they died because we spent our money fighting wars rather than getting food to those who needed it.

So, scientists, farmers and their advisers have saved the world from what we were told was the inevitability of global starvation.

Those same ‘saviours’ have never received the thanks of the world for their full bellies. Food is taken for granted.

The predictions of world starvation are with us again. There is international consensus that we must increase global food production by at least 40% or 50%, some say 70% or more by 2050 to feed an extra 3 billion people, bringing the world population up to 9 billion

The populations of Africa and Asia alone will increase by 2 billion. It’s a challenge of frightening proportions.

Norman Borlaug (he died in 2009 aged 95) was the first to say it at a conference in Mexico a decade ago and now the others are following his prediction that 80% of the increase in food production required to avert world starvation will have to come from land, which is already in production.

So, primarily, that means Australia, Canada, the USA, the EU and a few others, where population growth is slow or negative and who currently produce food excess to their domestic needs, will have to shoulder most of the burden to feed the extra billions, as any increase in South America, Africa and Asia will be taken up by increases in their populations.

National governments and maybe some companies, like airlines, may have to get serious about what seems to be the insurmountable problem of obesity. The average person in the United States and probably in Australia, consumes close to three times more calories than they need for a healthy life. I heard the other day of a man they could not take to hospital because the para-medics and even the ambulance was not equipped to handle his weight.

The same could probably be said about obesity for most of the Developed World, but even if food consumption can be reduced in those countries, it won’t be sufficient to meet the target of feeding another 3 billion people by 2050.

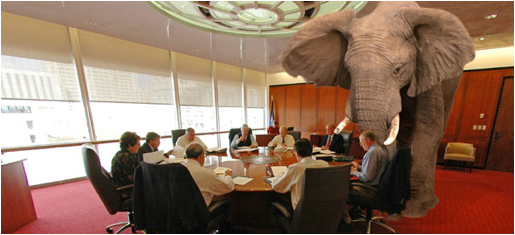

But there are a couple of elephants in the room of agriculture in the Developed World, which may well prevent it from repeating its stellar performance of the last forty years. They are elephants that not even Borlaug could control were he still with us.

These elephants have nothing to do with whether we can raise crop yields, because of course we can.

The complacent, uninformed, urban, replete, agricultural Luddites are the only ones who cannot see the challenges the world faces and cannot accept the advances being made by plant breeders of the 21st century, so they argue against the real advantages being revealed by biotechnology and its ability to help feed the world in 2050 and beyond.

Elephant # 1

There is a massive increase in the demand for so-called organic food and it’s only the rich who can afford it, which means the Developed World. The rich don’t care where their organic food comes from, even if it has to be flown in from another country, how’s that for a paradox?

They don’t seem to care that organic crops yield half that of conventional crops, so twice the area is needed to produce the same amount of food, which is hardly going to be helpful in the feeding of another 3 billion people. So the world of organics has to come up with some answers.

During the ‘Green Revolution’, Australia didn’t increase wheat yields per hectare at the same rate as the rest of the world, we made our contribution and doubled our wheat production by clearing more land and so nearly doubling the area cropped, and also by achieving modest yield increases compared to others, but there is no more land to clear. Ironically maybe, but there is now an ever increasing potential to increase yields as we begin to better understand the challenges. Imagine if we could grow cereals on salt affected land.

The other paradox, even the stupidity of those who hold the purse strings, is that we, Australia, are reducing our expenditure into Research and Development on cereals and according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, there is a direct correlation between a reduction in R & D and a slowing in productivity increases. So we have to ask the question do governments know what they are doing? Even worse, if they do know, why are they doing it. Is the political glow (even blue serge suit job), the ‘I told you so’ of a surplus in the national ‘Balance Sheet’ in five years more important than producing more food to avert a disaster for our children and grandchildren in 2050, which is just 36 years away?

The elephant in the room for Australian farmers is not, primarily, that the debt burden is becoming unmanageable, or that the real value of wheat and meat has been declining during the population explosion of the last forty years, it is that we don’t seem to have a plan for the future. We live year by year and regrettably Government by Government. Farmers in Australia live in a world of uncertainty and that uncertainty is not all caused by the weather.

These problems need urgent ‘whole of government’ attention if food production is to increase in Australia. There is little point in being ‘the most efficient farmers in the world’. Australian farmers have learned their lesson. There will be no more striving to increase production and at the end of the journey realizing there is often no correlation between productivity and profit. I mean real profit, a decent return on effort, a good return on investment. I don’t mean ‘survival’. In my view the word survive should be banned from ant discussions on farming and agricultural economics in Australia.

Is there a golden future for farmers?

The last forty years of producing food for twice as many people as there were in the sixties has contradicted the theory of the ‘experts’ over the last forty years, resurrected and unbelievably popular at the moment, particularly with those who don’t know what’s going on in the ‘real world of farming’, is that a world population of 9 billion will mean a golden future for food producers, all due to the theory of supply and demand; on past experience it will mean nothing of the sort.

On the contrary, the experience of the last forty years has demonstrated that as the population of the world has doubled and food production has more than doubled, there has been a decline in the real value of food to the producer and an increase in the profits of the all powerful supermarket chains.

The farmers of the Developed World will have to be paid more for the food they produce if productivity is to increase. Blind Freddy knows that. The question is can those who are going to need the food, pay for it, or will it have to go to them in the form of aid, paid for by the Developed World? Will that mean that the real values of unprocessed food like grain, will continue to decline?

Could the consequences of the aforementioned for Australian agriculture be a disincentive rather than an incentive to produce more? We know that profit and increases in productivity do not always go hand in hand, and it’s becoming imperative, for survival, to make a profit and reduced debt.

In most of the Developed World, except Australia, farm incomes are protected from unfavorable seasons and at times hostile terms of trade through all manner of government subsidies. In Australia there is the view that subsidies should only be discussed by consenting adults and then, preferably, in private.

The rather large elephants in the room of agriculture in the Developed World, which may well prevent it from meeting the challenges ahead and which could well cause, or at least put the world on the road to mass starvation, are both structural.

Structure problem #1

No matter where I look in the Developed World the average age of farmers is closer to sixty than fifty-five. In other words the Developed world is increasingly relying on old men and women as its primary agricultural labour force.

The situation in Australia is a mirror on the rest of the Developed World. Seventy two per cent of all farmers and farm mangers are aged 45 or over. Twenty four percent are aged between 45 and 54, and 23 per cent are aged 65 and over.

In the UK: ‘The age distribution of farmers had been fairly stable, with little change in the relative shares of different age groups, until 1997. Since then the proportion of farm holders aged 65 and over has risen, with over 30% of farmers aged 65 and over in 2005. The proportion of farmers under 35 has halved between 1990 and 2005 with only 3.1% of farm holders aged under 35. The average (median) age of farmers in the UK was 58 (Eurostat, 2005).’

In Canada there is a similar story, from the census in 2011 ‘The census highlights just how acute that need is becoming. As of last year, nearly half – or 48.3 per cent – of farm operators were 55 or older, compared to 40.7 per cent in 2006.

Just 8.2 per cent of operators were younger than 35 in 2012.

Move over the border to the USA, and this is what we find, ‘The aging trend has been decades in the making. Between 2002 and 2007 alone, the number of farmers over 65 grew by nearly 22 per cent.

New Mexico tops the list of states with the highest percentage of older farmers and ranchers at 37 per cent, followed by Arizona, Texas, Mississippi and Oklahoma.

For every one farmer and rancher under the age of 25, there are five who are 75 or older, according to Agriculture Department statistics.’

It doesn’t get any better in the EU, ‘In the 27 member states of the Union, more than half (55%) of the private farmers is over 55 years.’

Agriculture a useless degree?

Recently she moved on to another job, but the then U.S. Deputy Secretary for Agriculture Kathleen Merrigan showed her concern for the problem in America when she commented on a survey in that country, which put agriculture as No 1 in the ‘useless degree’ category.

“There couldn’t be anything that’s more outrageously incorrect,” Merrigan said. “We know that we’re not graduating enough qualified aggies to fill the jobs that are out there in American agriculture.”

What Kathleen Merrigan says must resonate with universities around Australian who are all reporting vacancies in the agricultural science courses.

There was a report in the Australian rural press recently of thousands of vacancies for agricultural science graduates, especially agronomists.

Add to all of the above the shortage of skilled farm labour, which again seems to be a world wide problem

We should know we have a problem when we have to rely on backpackers for seeding and harvest.

If Western Australia is representative of the rest of Australia, then we are in a mess as we no longer have that vital cog, sufficient young people, in the structural chain connecting us with the future.

Muresk Agricultural College (as it once was) is going or has gone, the farm is to be sold. Muresk was the place, which trained the farmers and farm managers of the future. Has someone made the decision we don’t need young farmers? If they have who made that decision and why? We certainly don’t have sufficient young farmers coming along who understand the increasingly scientific world they live in. But then we could run out of scientists as well.

Muresk should never have been made into a pseudo university. It should have remained as a tertiary college to teach young people the practical skills needed to farm and sufficient knowledge and ability to understand the advances made in agricultural science so they could apply them in their everyday work, in the paddock, on the farm

So how the heck is the Developed World going to meet the challenge of increasing food production by 50%, 60%, 70% by 2050 — pick a number, it doesn’t really matter which one.

There is, maybe, just maybe, a light at the end of the tunnel, but it might also be a train heading towards us with its light on.

Structure problem #2

Looks like we are not on our own, the same thing is going on in of all places, China; but there is a difference, a big difference, look at the numbers:

Graduates go off land despite talent shortage

Updated: 2011-04-05 14:36

By Lu Chang (China Daily)

‘Of the 1.3 million who graduated from China’s 43 agricultural universities from 2001 to 2010, only 500,000 are working in the agricultural sector, the latest agricultural technology development guidelines from the State Council, China’s Cabinet, said.

Yet, the demand for agricultural graduates, particularly for technicians and engineers, has grown as China continues to implement modern technology.

Agricultural universities now face the challenge to recruit talented students. “We just don’t have enough students enrolling in our program,” said You Jie, a professor in the college of agricultural sciences in China Agricultural University in Beijing.’

What is interesting is China is showing and even Australians are predicting, an ever increasing interest from China in Australian agriculture.

The Chinese are buying Australian farms — rumours abound they want more. Some say they want to ‘buy’ the Tasmanian dairy industry and export everything to China.

So with an ageing population of Australian farmers, many heavily in debt, many who want to sell and at least have a few years without the worry of rain and drought, and a government, even an Australian body politic that doesn’t understand their problems, maybe some of the 130,000 agricultural science graduates China produces every decade could just be the answer? — Especially if they bring their chequebooks with them. Language problems? English is now mandatory in schools and universities in China.

How did we get in this mess?

It’s a bit like the old crocodile and swamp story, which goes like this:

‘When you are up to your knees in crocodiles, the gun is running hot and the ammunition low, it’s a bit difficult to think about draining the swamp, then the crocodiles will go away of their own accord.’

As an industry we have to decide whether we are a tacticians, croc shooters for the short term, or strategists, swamp drainers, for the long term.

‘Will we leave this place in better condition than we inherited from our fathers’, is a question that should be put to every man and woman who considers themselves as a leader in Australian agriculture.