In July of this year a $22 billion proposal by Sun Cable Pty Ltd, a company which is backed by by two Australia billionaires Fortesque Metals founder Andrew Forrest and and Atlassian co-founder (with Scot Farquhar) Mike Cannon-Brookes was granted ‘major project status’ by the Australian Government to investigate the building in the Northern Territory of a massive 10-gigawatt solar farm (40 million panels) coupled to a 30Gwh storage facility, which I presume means a big battery.

In July of this year a $22 billion proposal by Sun Cable Pty Ltd, a company which is backed by by two Australia billionaires Fortesque Metals founder Andrew Forrest and and Atlassian co-founder (with Scot Farquhar) Mike Cannon-Brookes was granted ‘major project status’ by the Australian Government to investigate the building in the Northern Territory of a massive 10-gigawatt solar farm (40 million panels) coupled to a 30Gwh storage facility, which I presume means a big battery.

Tag: subsidies

The Myth of a Level Playing Field.

Mr Albanese, the Leader of the Australian Labor Party, has a poor grasp of Australian political history.

Mr Albanese recently roundly criticised Treasurer Josh Frydenberg for channeling Margaret Thatcher and the policies employed by her to ensure the much needed economic recovery in the UK following Prime Minister James Callaghan and his self inflicted demise in his ‘winter of discontent’ of 1978/79.

Callaghan finally decided to call a General Election in 1979 after the country had been ravaged for years by high inflation and unemployment. In 1978/79 strikes in both the private and public sectors almost crippled the country.

Uncollected rubbish was left to rot in the streets of London, the dead were not being buried, there was a mounting national shortage of food and fuel due to the truck driver’s refusing to work, which all combined to cause a crisis so bad the government considered declaring a state of emergency and mobilising the troops to take over vital services.

Uncollected rubbish was left to rot in the streets of London, the dead were not being buried, there was a mounting national shortage of food and fuel due to the truck driver’s refusing to work, which all combined to cause a crisis so bad the government considered declaring a state of emergency and mobilising the troops to take over vital services.

Eventually, after strikes which were violent at times, the unions got the wage increases they wanted but it was a pyrrhic victory for them. The country, the people had had enough of the militant unions shambolically and carelessly wrecking the economy, so when they got the chance they elected Margaret Thatcher to be the first woman to be Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

Eventually, after strikes which were violent at times, the unions got the wage increases they wanted but it was a pyrrhic victory for them. The country, the people had had enough of the militant unions shambolically and carelessly wrecking the economy, so when they got the chance they elected Margaret Thatcher to be the first woman to be Prime Minister of the United Kingdom.

In eleven years Margaret Thatcher rebuilt the UK economy and made it world competitive and respected if not liked around the world.

Albanese rejected what he saw as Frydenberg’s move to Thatcherism in favour his more Keynesian way of more and more government spending to build infrastructure and particularly social housing, for which, admittedly, there is a great need all over Australia.

Does Mr Albanese not know or does it suit his argument not to recognise that Bob Hawke and Paul Keating were the first Australian leaders to employ economic rationalism — they were the first true disciples of Margaret Thatcher?

They were Thatcherites through and through, they introduced Free Trade Agreements, globalisation and the ‘market economy’ to Australia.

It was under their government that we started to see the demise of the Australian manufacturing and food processing industry — all in the name of being ‘world competitive’.

It was also the start of a deliberate campaign to reduce the political power of agriculture in Australia.

The National Farmers’ Federation and their Dreamtime.

The National Farmers’ Federation of Australia, the National Party and the Liberal Party, together with the Australian Labor Party, all believe that Australian agriculture can raise its production to $100 billion at the farm gate by 2030.

The National Farmers’ Federation of Australia, the National Party and the Liberal Party, together with the Australian Labor Party, all believe that Australian agriculture can raise its production to $100 billion at the farm gate by 2030.

That is an increase of 66.6% on the production of 2018 or an annual increase of about 4%, and presumably, though they haven’t said as much, they all expect the producers to make a profit every year— which is more than they do now — but they don’t tell you that.

There are some truly grim truths about the financial ill-health of Australian agriculture and they are all produced by government statisticians and the Reserve Bank of Australia.

Why these grim truths were ignored by the NFF when they set their $100 billion target, and why that target was endorsed by those who determine the the agricultural policy of this country, is for them to answer.

It would appear that there isn’t a minister for agriculture in Australia today, at both the federal and state level, who had any qualifications or hands on experience in agriculture or (agricultural) economics prior to being appointed to their agricultural portfolio. Even worse they all seem to have many other portfolios and being only human, the time they can spend on agriculture has got to be limited.

This must mean that our ministers of agriculture rely on advice from the federal and state government agricultural bureaucracies, the state and natio nal farmer organisations and those stalwarts of Australian agriculture, the MLA and the GRDC, who are kept fat by the millions of dollars of compulsory deductions levied on producers.

nal farmer organisations and those stalwarts of Australian agriculture, the MLA and the GRDC, who are kept fat by the millions of dollars of compulsory deductions levied on producers.

Ben Rees; B. Econ.; M.Litt. (econ.)

Ben is a seriously underutilized elder statesman in Australian agriculture, probably because he deals in facts, not emotional subjective dreaming in which many in the so-called high echelons of agriculture in this country indulge.

Ben recently presented a paper to the Royal Society in Queensland. For the complete article Rural Debt and Viability click on the link above and then at the bottom of the page when it comes up click on: Ben Rees on rural debt and viability. I will try and post the complete article on this website as soon as I can.

You may not agree with Ben’s opinion — but it will make you think and make you wonder what the so-called leaders of agriculture do in their working time — time, which we all pay for.

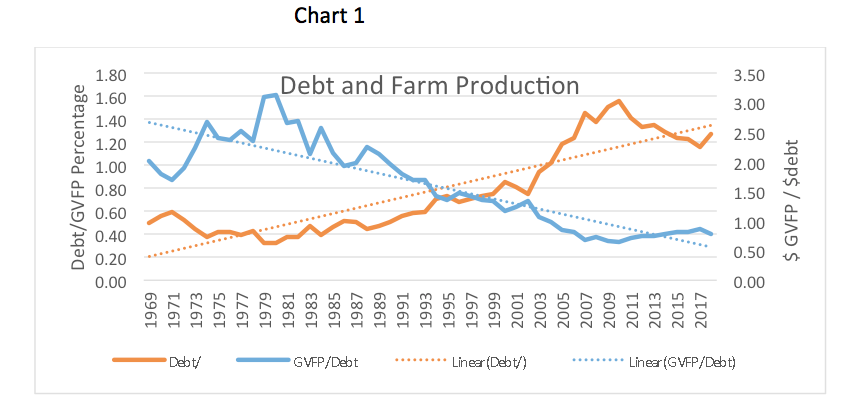

Just a glance at Graph 11, lifted from one of Ben’s papers, demonstrates that the problems facing Australian agriculture today have not been caused by drought and will not be fixed by building new dams — the rot started years ago — it’s called debt.

This is what Ben writes about Rural debt, gross value of farm production and net value of farm production: Graph 11 illustrates the impotence of the RBA to deliver required real sector policy. By 1983, GVFP was rising at the expense of NVFP. Beyond 1983, any relationship between debt and GVFP NVFP evaporates. Upward inflections in the debt curve are identifiable in 1988 and 1993 following tariff reform. Any relationship between GVFP and debt cease to exist beyond 1993; and; finally in 2003-04 the debt curve rises steeply cutting through the GVFP curve. Finally the GFC effect slows down the rural appetite for debt. From 2017, the debt curve gradient begins rising more steeply than the GVFP curve indicating that rural production is again being funded by rising indebtedness. Some good old fashioned fiscal policy was badly missing. (Ben Rees)

Nobody involved in agriculture providing they can understand basic economics like 2 + 2 = 4 – 4 = 0 can fail to see the the agricultural tragedy contained in Graph 11.

Australian agriculture has been on a productivity binge for the last fifty years. Since 1990, the gross value of farm production has grown from about $20 billion to where it is today at about $60 billion, a growth of some $40 billion or 200% in thirty years. Whereas the net value of farm production has grown from about $5 billion to about $20 billion an increase of some 300% during the same period, which looks great until we examine the debt, (red line) which has grown from $10 billion to just under $70 billion during the same period, an increase of an astounding 600%.

This increase in farm production has occurred as the number of farms has decreased. In 1970 we can see from Graph 11 that rural debt was just a few billion dollars and there were about 180,000 farms, the numbers are too small to calculate. By 2016 farm numbers have reduced to 100,000 (the NFF claims there are just 85,000 farms) and the debt has risen to ~$77 billion and by 2019 that debt has risen to $80 billion.

If we divide 100,000 by $80 billion it gives us an average farm debt of $800,000, and that is for all farms producing over $25,000. It doesn’t end there. In a publication produced by the federal Department of Agriculture and Water Resources for the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking and Financial Services Industry in 2018, it is claimed that 70% of the aggregate broad acre debt was held by just 12% of farms.

On average these were large farm who produced some 50% of the total value of broad acre farm production in 2016-17. It should be noted that debt figure does not include the total credit facility limit which was estimated in the same paper at a whopping $86 billion. For many with large cropping enterprises an annual overdraft facility can, in the short term, double their debt exposure. No wonder so many feel as though they are standing on the edge of an abyss when the weather does not perform as planned.

The increasing debt levels have followed the increase in land values as shown in Figure 1. The ability to borrow against an asset, as we all know, has nothing to do with the ability to repay a debt. If the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking and Financial Industry revealed anything it was that the banks were more than willing to lend against rising equity levels without determining whether the debt could ‘reasonably’ repaid by the borrower. It also showed that they showed no mercy to those who, for whatever reason, defaulted. Rural debt continues to rise at over a billion dollars a year.

However, the alarming result of the spiraling debt, highlighted by Ben Rees, is that $1 of debt is now needed to produce 64 cents of production as shown in Chart 1. Whereas in 2003/4 one dollar of debt produced $1 of production and in 1989 one dollar of debt produced $2.14 of production. What kind of crazy economics is that?

The billion dollar question must be, ‘How many dollars of debt will be needed to generate one dollar of production on the road to achieving $100 billion at the farm gate?’ Maybe the NFF have the answer?

Have another look at Graph 11 at the widening gap between net value of production and gross value of production. That graph begs the question whether there will be an acceptable margin between costs and returns to repay what now seems to be an inevitable mushrooming of debt.

Figure 1 Thatcherism

Thatcherism

Not many in the Australian Labor Party today will recognise that those two great reformers, Hawke and Keating, were devout disciples of Margaret Thatcher, and as a result of their adoption of ‘Thatcherism’ and its mantra of ‘the market economy’ Australian agriculture suffered as market support was gradually reduced to where it is today — virtually non existent.

What Hawke and Keating and all successive Australian Governments have failed to recognise is that the adoption of the market economy philosophy around much of the free world in the eighties and nineties did not affect the huge ‘market support’ or subsidies paid to agriculture.

Without US$580 billion in annual subsidies farmers in the EU , the United States of America and almost every country around the world could not survive.

Australian producers receive world prices for their exports and have some of the highest costs and the lowest yields in the world, particularly in wheat production — their competitors also receive world prices for what they produce, but they also receive government subsidies.

Where price is king in the food markets of the world it isn’t rocket science to conclude that Australian producers face severe competition in both our domestic and overseas markets.

Have a look around the supermarket shelves in Australia and see what is imported, and what, once-upon-a-time, was grown and processed in Australia.

Australian supermarkets scour the world for the cheapest food they can buy and every time they bring more food into Australia, they put another nail in the coffin of Australian agriculture.

One of the reason that rural debt is increasing is because of land purchase. Farmers have been buying more land in an effort to benefit from an economy of scale. Fewer workers because the sheep have gone has meant bigger machinery, bigger machinery means bigger borrowing. Again, it ain’t rocket science. The quwstion is, has it worked?

The Cost of Debt Funded Production.

Let us now look through Ben Rees’ prism at farm debt over time and what producers have been able to produce with that debt, Ben writes:

Chart 1 below empirically analyses debt to output as a policy efficiency performance indicator. The orange curve is Debt/ Gross Value Farm Production (GVFP) whilst the blue curve is calculated by dividing GVFP/ Debt.

2.1 Performance Indicator Outcomes

- Steeply positive gradient long term orange trend curve ( Debt/GVFP)

- Orange curve suggest that production has been debt dependent

- Steeply negative gradient blue long term trend curve ( GVFP/Debt)

- From 1984, declining efficiency as debt relentlessly consumes production

- In 1989, $1 debt produced $ 2.14 in output.

- By 2003-04, $1 of debt produced $1 of output

- In 2010, $1 of debt produced 64 cents in production

- From 1993 to 2013, sectoral performance lies below the negative sloping blue trend curve.

By any reasonable assessment, Rural Adjustment has not delivered theoretically expected outcomes from economies of scale, increased efficiency and rising productivity. Post 2003-04, both curves identify debt funded output as inefficient and unstable. Any other sector would have demanded a change in policy direction; but, agricultural leaders appear to have strongly believed the rhetoric of market theology that reduced farmer numbers structuring economies of scale would ensure long term sectoral viability. That simplistic arithmetic approach by industry leaders, major political parties; and, commentators has been a gross violation of established economic knowledge.

Ben is right. We must conclude that there is no plan for agriculture in Australia apart from that being offered by the NFF and endorsed by all political parties. What does that say for their understanding of established economic knowledge?

Is debt going to strangle Australian agriculture?

In  October 2018 the National Farmers’ Federation (NFF) presented Australian agriculture with an enormous challenge —a vision for the future:

October 2018 the National Farmers’ Federation (NFF) presented Australian agriculture with an enormous challenge —a vision for the future:

17th October 2018

The National Farmers’ Federation (NFF) has laid down a bold vision for the industry: to exceed $100 billion in farm gate output by 2030.

Based on our current trajectory, we know industry is forecast to reach $84 billion by 2030. This suggests that we still have significant work to do over the next 12 years if we are to achieve our vision.

To support their plan, the NFF have developed a road map which tells us how Australian primary producers from wheat, sheep and beef producers to bee-keepers and everyone in between what the ‘road’ is to the national farm gate producing $100 billion by 2030.

The NFF road map is complicated. I wonder how many farmers, agricultural producers and their advisers and critically, their bankers, those who lend them money, have read it — and more importantly, been able to understand both the map and their position on it?

There is no doubt that agriculture in Australia requires re-structuring. Whether the NFF Road Map is the way forward I leave for you to decide.

Is $100 billion by 2030 now the clarion cry of Australian agriculture?

To produce $100 billion of farm gate output by 2030 will require a 66.6% increase measured in dollars of production across the face of Australian agriculture in a little over ten years. Seriously? Given our recent history of growth is that figure realistic? 66.6% growth would require an annual 4% nominal growth rate in the Gross Value of Farm Production (GVFP).

There are three ways of achieving the NFF vision:

- Assume that the gross value of farm production (GVFP) will increase by 66.6% and assume that yields will not and producers will make a profit or:

- Assume that yields by will increase by 66.6% and prices will do what they seem to have by-and-large done over the last ten years and remain constant or decline and producers will make a profit.

- A mixture of both of the above and assume that rural debt will continue to increase and producers will still make a profit.

A 66.6% increase in the dollars generated at farm gate in what is now just 10 years is a massive ask. Maybe the NFF are banking on new rural industries to help reach the target and well they may, but realistically, surely, the heavy lifting will have to be done, as usual, by the producers of wheat and beef and to a lesser extent canola, wool and sheep meat.

If there is one common thread that runs through all of the research I have put into this article so far, it is that Australian agriculture faces global challenges from ernest competitors who can produce and ship product into markets where we are active at a price which Australian producers would find and more importantly are already finding, difficult to match.

Our reputation for quality is appreciated by those who can afford it, but as markets expand, like the exponential growth of the middle class in Indonesia and China, so too does the market for products of a lesser quality than that which is available from Australia. Prime examples are buffalo meat into Indonesia at the expense of Australian beef and Australia’s massive loss of market share to Argentina and the Baltic States in the wheat market of the same country. The last one is hard to explain when we can almost see Indonesia from two of our major export ports in Western Australia.

What do the Banks think?

The Commonwealth Bank are not as optimistic regarding growth as the NFF, their view, as a major lender, is that production will fall across all agriculture mainly due to a drop in rainfall. A 50% drop in grain production and a 40% drop in livestock by 2060 is predicted. If Australian agriculture is to reach the NFF target of $100 billion by 2030 it will need the support of the CBA.

In contrast to the Commonwealth Bank there is a publication called Australian National Outlook – 2019. The joint Chairmen of Outlook 2019 are Dr Ken Henry AM when he was Chairman of the NAB and David Thodey AO, Chairman CSIRO. The publication is a joint effort by over 50 contributors from some 24 organisations who forecast a better picture than the Commonwealth Bank, but with many challenges for agriculture and for the nation, it is worth a read.

Beware, it is complicated, ambitious and apart from some wild assumptions on climate change, (my personal bias) a very well thought out document, and in many ways it is a pity it is not a fundamental part of the national conversation on the future of agriculture.

It makes one wonder whether those in the NFF who claim to lead this fine industry really understand, seek or accept the considered opinion of others who are already major participants in the industry of agriculture in this country. What is of note is that the Australian National Outlook forecasts a far more modest growth to $80 billion in agricultural production but by 2060, rather than the NFF target of $100 billion by 2030.

The NFF say they consulted widely before settling on the $100 billion target: The NFF led a 6-month consultation effort to inform the Roadmap. It began with a Discussion Paper which distilled insights from leading experts, before commencing a nationwide roadshow, where we spoke to over 380 farmers and other industry experts to field their views. As we consolidated this feedback, we engaged regularly with industry stakeholders and experts to ensure the ideas we’re putting forward are credible and impactful.

The NFF say they have consulted with 380 farmers. They claim there are 85,681 farmers in Australia. So they consulted 0.4435055% of farmers in Australia in the preparation of their Road Map! Hardly statistically significant.

It is also reasonable to ask whether the NFF consulted with the CSIRO, the NAB and any the fifty other industry brains who contributed to the Australian National Outlook 2019 who have a different view of the future to that of the NFF.

The has been a massive loss of knowledge and skills in agriculture.

What really shook me from Ben’s analysis of the agricultural economy, is the loss over the last thirty years of experience and skill in agriculture — this must surely present this industry with a huge challenge? Again, this is from Ben’s paper:

4.1 Performance Indicator Employment

ABARES commodity statistics for 2018[i] , shows agricultural employment peaking historically in 1990-91 at 387, 000; but, falling to 279 000 in 2017-18 (29%). Meanwhile for Australia, over the same period, employment rose from 7.8 million to 12.5million (60.3%). It stretches the mind to think the decline in agricultural employment alongside such strong national employment growth is explainable by consolidation of farm size and applied technology. Agricultural policy needs to accept responsibility for this employment outcome.

The reality is that structural industry reform began with the 1988 tariff reductions which were ratcheted up again in 1991. Orderly marketing of both major industries wool and wheat were discontinued over 1989-90. It cannot be explained as mere coincidence that agricultural employment began to decline from its peak in 1990-91 as a result of technological adoption by the farm sector at the same time structural reform of agriculture began in earnest.

Chart 3 identifies empirically that agricultural employment contracted strongly across broad-acre agriculture; and, the self – employed small scale farmer. Broad-acre employment decline appears from 2002 coinciding with the worsening of the Millennium Drought. The real loss of employment though lies in the self -employed and owner manager classification from 1992 onwards. The impact of the self- employed owner manager is particularly important as that group comprised largely the part time skilled labour force residing in rural Australia. Policy driven policy of Rural Adjustment “shipping out” small inefficient farmers would seem a more logical contributor than technology.

[i] ABARES commodity statistics, 2018, Table 1.2 , Australian employment by sector.

- Long term decline in broad acre employment 52% between 1992 -2018

- Self-employed fall 71.4% between 1992 to 2018 (192 000 to 55 000)

- Millennium Drought emerging1997-2009

- GFC 2009- 2013

- 2013+ Current Drought

The decline in agricultural employment whilst employment in the wider economy continued to rise strongly is a damming policy indicator. If agriculture was likened to a private firm, a clean out of the board, senior management, and advisors would be expected.

How true!

In the next issue of Global Farmer we will examine whether our main agricultural industries of beef, sheep and grain, are capable of playing their part on the road to achieving $100 billion by 2030. The question must be asked can they do it and more importantly, who has already claimed they can, because somebody has? Haven’t they?

Take control of the wheat industry.

It’s time to talk seriously about re-structuring the wheat industry in Western Australia and probably Australia. It’s time that wheat growers demanded recognition for the contribution they make to the national economy. When was the last time you heard the Prime Minister or the immediate past minister (Barnaby) or the current Federal Minister for Agriculture, or even the current crop of state ministers talk about the financial health of the producers of Australia’s biggest cash crop?

It’s time that the wheat industry faced reality, the bureaucracies they fund have failed them. Have a look at what Negative Profit means, it’s a euphemism for loss; then read on and tell me what you think, tell me if I am wrong in calling for change.

There will be no Australian wheat industry in 23 years time.

In the last issue of the Global Farmer I discussed the need for change based on a strategic plan for the behemoth called Australian agriculture. It is not possible to look at the whole until the parts have been examined.

To start with the wheat industry is logical and relevant considering this is the time of year to review last year and make plans for and give a commitment to the next season and beyond.

The headline says it all, based on current trends, the wheat industry in Australia will be gone in twenty three years. If you are having difficulty in trying to remember what was going on in Australian agriculture twenty three years ago, it was five years after the wool price crash and we were all being told to get rid of our world beating merino sheep. That is how close we are to the demise of the Australian wheat industry. It won’t happen like the wool crash, for those who refuse to recognise the signs it will be a slow, painful and imposed exit.

Continue reading “There will be no Australian wheat industry in 23 years time.”

Free Trade Agreements – Are they an Oxymoron?

Stop Press.

Why do we put up with governments who do nothing for our national security?

It is Friday March 3 2017 at 08.00 hrs. On ABC AM this morning at about 10minutes 29 seconds into the programme, Andrew Davies from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, announced we only have about three weeks supply of petrol in store in Australia — three weeks!! (search in the archive for the AM programme of March 3, otherwise you will get today’s programme) He raises the possibility of any tension between America and China could close off the sea route through the South China Sea and so cut of our supply of fuel from Singapore, on whom we are almost totally reliant. The story gets worse because it is not a new problem, there is a story in The Conversation from 2013 which forecast an impending fuel supply crisis unless the government of the day took strong action. It didn’t happen. The point needs to be made made it wouldn’t need a full blown war to disrupt fuel supplies, just a disagreement between the world super powers and the shipping routes that service Australia could close and we would run out of not only fuel but everything we import by sea.

Continue reading “Free Trade Agreements – Are they an Oxymoron?”

The Farmers in Europe are Revolting

The value to Australian agriculture from Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) can be put into perspective when we contemplate having to compete against the home grown subsidised produce of much of Asia. If their ‘home grown’ produce, for instance beef, is subsidised, then to compete we have to be price competitive with a subsidised product – can we compete with subsidised agriculture? Only if we can sell at a price that is competitive, which may mean lower, than the subsidised product. For decades, since the seventies, Australian farmers have been duped by politicians of all colours and from agriculture, that ‘market forces’ and a ‘free market economy’ will eventually prevail. Fig 1 and Fig 2 (later) puts a lie to that propaganda and shows what it has cost. To compete we can see that Australian farmers ‘chased’ the ‘get big or get out’ mantra of the 70s with debt. More of that later.

As a child growing up in post-war Britain anything from Australian from wool to meat, to apples both fresh and dried, dried fruit and the delicious Sunday treat of Australian canned peaches, was a sign of absolute quality. The only exception to that rule was the processed cheese we were served in the army in the nineteen fifties. I am sure it had been imported during the war. Second World War, I think – maybe?

How times have changed. Britain is part of the EU, the European Union. This is what the EU say about themselves:

The EU is an attractive market to do business with:

- We have 500 million consumers looking for quality good

- We are the world’s largest single market with transparent rules and regulations

- We have a secure legal investment framework that is amongst the most open in the world

- We are the most open market to developing countries in the world

That is a proud boast and if you look at the link you will see the truth of it. They are indeed a powerful union – even a nation. To protect their agriculture the EU pays their farmers subsidies amounting to about US$100 billion a year.

In ‘Farming on Line’ a UK farming journal came this alarming news on Wednesday 29 July 2015. Copa and Cogeca warned at the EU Milk Market Observatory meeting today that the EU dairy market situation has deteriorated rapidly in the past 4 weeks, and without EU action, many producers will be forced out of business by Winter. Speaking at the meeting, Chairman of Copa-Cogeca Milk Working Party Mansel Raymond said “The market is in a much more perilous state than it was 4 weeks ago, with producer prices far below production costs. It’s a critical situation for many dairy farmers across Europe”.

Who or what are ‘Copa’ and ‘Cogeca’? ‘Copa’ was formed in 1959 to represent farmers within what we now know as the EU, it had 13 affiliates at that time. It now speaks in Brussels for sixty farmer organisation’s within the EU and another thirty six affiliates like Norway and Turkey, outside of the EU, but in Europe.

Cogeca? Straight off their website : On 24 September 1959, the national agricultural cooperative organisations created their European umbrella organisation – COGECA (General Committee for Agricultural Cooperation in the European Union) – which also includes fisheries cooperatives.

COGECA’ s Secretariat merged with that of COPA on 1 December 1962.

When COGECA was created it was made up of 6 members. Since then, it has been enlarged by almost six and now has 35 full members and 4 affiliated members from the EU. COGECA also has 36 partner members.

So ‘Copa & Cogeca’ to our antipodean ears may sound like a dance from South America, is in fact a very powerful agricultural lobby in Brussels and the Parliament of Europe. Stuck down here at the other end of the world we tend to forget that Europe is now a bigger trading bloc than America and China.

Vive la France !

French farmers are a passionate lot and in support of Copa & Cogeca, last month on warm summer days in the middle of the tourist season they dumped loads of animal manure in the middle of Paris and other cities. For those who don’t know what the machine below is, it’s a ‘muck spreader’. Normally filled with animal manure and coupled to the power take off on the tractor it ‘spreads’ the manure on the fields or paddocks. In this case it looks like it is being used to ‘clean’ windows – on a bank perhaps?

A Lidl of what you fancy does you good.

European Bank Subsidised Lidl Expansion with A$1200 million.

The companies, owned by the large retail company Schwarz Group and controlled by one of Germany’s wealthiest families, received loan funding from a little-known wing of the World Bank and from the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). There is no suggestion there was anything ‘wrong’ with the funding, as you will see it is part of the specific mandate of these organisations funded by taxpayers and owned by governments to encourage local development, in this case in Europe.

The German Federal government, on their website has been heavily promoting both Lidl and Aldi in America to help it to become established in that country and, no doubt, sell food that has been made or produced in Germany. Lidl like Aldi, also sell a range of German made hardware, electrical goods and many other things.

Aldi already have stores in Australia and it is understood they plan many more. Lidl are also planning a chain of stores throughout Australia. In what seem like a few years in the UK they have secured over 10% market share and are causing both Tesco and Waitrose, the two biggest food retailers in the UK, to review their business plans.

They have made no secret about being ‘aggressive’ with their entry into America. Maybe interesting times for the Australian consumer, but what about the producers and what few processors are left, what of the future for them?

Pigs in Australia – Minister Joyce replies with the usual spin.

Q. How unlevel is the ‘playing’ field? A. It’s a hill.

I have the time and I have the intense interest in food trade and objective to see Australian agriculture, once again, world competitive.

We really are a small player in world agriculture. We grow just 5% of the world’s crop. We jump up the ladder as a trader where we come in at between 12 and 15 in world rankings. That’s why the big boys want to play here. If you live 200km from the port it’s costing you between $60 and $75 a tonne to get you grain to port.

www.aegic.org.au/…/supply–chain–costs-impact-global-competitiveness.a…

I know we are a world leader in the export of beef but I’m looking for a volunteer to tell the full story. From what I am told we could do so much better both domestically and for export.

One of the reasons we don’t get a lot of international news is because we are obsessed it seems to me, with domestic politics and in agriculture with domestic agricultural politics. It is hard to imagine an industry with so many organisations, committees, Peak Bodies, and people who claim to speak for one particular group or another, gossipers and rumour mongers. Yet in spite of that, we are deeply dependent on the export markets for our commodity products, cereals, meat and wool and to a lesser extent on perishable goods, fresh fruit and vegetables. Quite fascinating that WA is exporting fruit and veg to Bali, maybe it reduces the Bali Belly? Continue reading “Q. How unlevel is the ‘playing’ field? A. It’s a hill.”