The value to Australian agriculture from Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) can be put into perspective when we contemplate having to compete against the home grown subsidised produce of much of Asia. If their ‘home grown’ produce, for instance beef, is subsidised, then to compete we have to be price competitive with a subsidised product – can we compete with subsidised agriculture? Only if we can sell at a price that is competitive, which may mean lower, than the subsidised product. For decades, since the seventies, Australian farmers have been duped by politicians of all colours and from agriculture, that ‘market forces’ and a ‘free market economy’ will eventually prevail. Fig 1 and Fig 2 (later) puts a lie to that propaganda and shows what it has cost. To compete we can see that Australian farmers ‘chased’ the ‘get big or get out’ mantra of the 70s with debt. More of that later.

As a child growing up in post-war Britain anything from Australian from wool to meat, to apples both fresh and dried, dried fruit and the delicious Sunday treat of Australian canned peaches, was a sign of absolute quality. The only exception to that rule was the processed cheese we were served in the army in the nineteen fifties. I am sure it had been imported during the war. Second World War, I think – maybe?

How times have changed. Britain is part of the EU, the European Union. This is what the EU say about themselves:

The EU is an attractive market to do business with:

- We have 500 million consumers looking for quality good

- We are the world’s largest single market with transparent rules and regulations

- We have a secure legal investment framework that is amongst the most open in the world

- We are the most open market to developing countries in the world

That is a proud boast and if you look at the link you will see the truth of it. They are indeed a powerful union – even a nation. To protect their agriculture the EU pays their farmers subsidies amounting to about US$100 billion a year.

In ‘Farming on Line’ a UK farming journal came this alarming news on Wednesday 29 July 2015. Copa and Cogeca warned at the EU Milk Market Observatory meeting today that the EU dairy market situation has deteriorated rapidly in the past 4 weeks, and without EU action, many producers will be forced out of business by Winter. Speaking at the meeting, Chairman of Copa-Cogeca Milk Working Party Mansel Raymond said “The market is in a much more perilous state than it was 4 weeks ago, with producer prices far below production costs. It’s a critical situation for many dairy farmers across Europe”.

Who or what are ‘Copa’ and ‘Cogeca’? ‘Copa’ was formed in 1959 to represent farmers within what we now know as the EU, it had 13 affiliates at that time. It now speaks in Brussels for sixty farmer organisation’s within the EU and another thirty six affiliates like Norway and Turkey, outside of the EU, but in Europe.

Cogeca? Straight off their website : On 24 September 1959, the national agricultural cooperative organisations created their European umbrella organisation – COGECA (General Committee for Agricultural Cooperation in the European Union) – which also includes fisheries cooperatives.

COGECA’ s Secretariat merged with that of COPA on 1 December 1962.

When COGECA was created it was made up of 6 members. Since then, it has been enlarged by almost six and now has 35 full members and 4 affiliated members from the EU. COGECA also has 36 partner members.

So ‘Copa & Cogeca’ to our antipodean ears may sound like a dance from South America, is in fact a very powerful agricultural lobby in Brussels and the Parliament of Europe. Stuck down here at the other end of the world we tend to forget that Europe is now a bigger trading bloc than America and China.

Vive la France !

French farmers are a passionate lot and in support of Copa & Cogeca, last month on warm summer days in the middle of the tourist season they dumped loads of animal manure in the middle of Paris and other cities. For those who don’t know what the machine below is, it’s a ‘muck spreader’. Normally filled with animal manure and coupled to the power take off on the tractor it ‘spreads’ the manure on the fields or paddocks. In this case it looks like it is being used to ‘clean’ windows – on a bank perhaps?

In contrast, the stoic British dairy farmers have been disrupting the traffic on motorways, protesting outside retail outlets, ‘raiding’ supermarkets and filling trolleys with ‘below cost of production’ milk then leaving the loaded trolleys at the checkout.

The UK National Farmers Union and the ‘Farmers Weekly’ the leading agricultural journal in the UK, have supported farmers by printing posters informing consumers that farmer’s costs are bigger than their returns and that is forcing a dairy farmer a day out of business.

A few days ago Arla, Britain’s biggest milk co-operative, announced a price cut of 0.8 pence per litre – meaning it now pays 23.01 pence a litre (A$0.48) to its UK members.

However, farmers say it costs between 30 and 32 pence to produce each litre of milk, with many smaller producers already being driven into financial difficulties.

Reports from Northern Ireland claim producers have been paid 19 pence a litre.

Milk – It’s a world-wide problem.

Last week in New Zealand, Fonterra – New Zealand’s biggest exporter – lowered its farmgate milk price for 2015/6 to $3.85 a kg of milk solids, down from a previous forecast of $5.25 a kg. A price around $5.70 is regarded as breakeven for many farmers. Both the banks and Fonterra have committed to helping dairy farmers, many of whom switched from prime lamb production to capitalise on the worldwide demand for milk products – again, sadly, the price crash can in part be attributed to lack of demand out of China. One minute China is there demanding more milk and the next minute she’s gone – it is perplexing – the relaxation of the one child policy in China should have increased the market for milk products, not caused it to collapse.

Why does China keep on cropping up in these crises? At the moment it’s milk prices driven below the cost of production. Now that the railways and the ports have been built with what everyone believed were ‘high’ iron ore prices, the price has halved and caused anguish among many small iron ore producers. Australia’s iron ore market is controlled by China. China is a major buyer of Australian coal and gas. China absolutely controls the Australian wool market. The world seems to be rushing to meet what China has convinced the world will be an unprecedented demand for food in China – we can we now ask ‘at what price?’.

Below is part of a story in the Financial Review last year:

The success of New Zealand’s dairy sector – where milk volumes have more than doubled since 2000 to 20 billion litres – has come at the expense of red meat.

New Zealand farmers have been making far better returns from dairy farming so have, en masse, ditched sheep and beef cattle for milking cows.

The number of sheep has fallen almost 60 per cent since the 1980s to about 30 million. Analysts expect numbers to continue falling. Forget 10 sheep per Kiwi. There are now 6.7 sheep for each of the New Zealand’s 4.5 million inhabitants.

Milk? – Lamb? – Take your pick – they both lose money in the EU.

A friend of mine in England, a retired farmer, remarked in a letter that all is not well with British agriculture, commenting milk, lamb and cereals all in the doldrums.

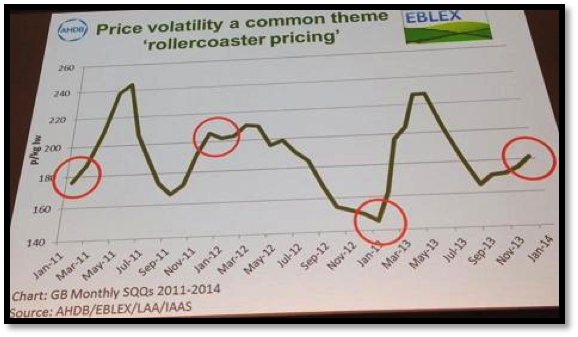

The graph below shows how unpredictable the lamb market has been for UK producers. New Zealand lamb (and Australian) is seen as the ‘cheap import’ and rightly or wrongly is blamed for the volatility in prices. Looks like they have the same problem in the UK as we have in Australia and that is UK retailers like Tesco and Morrisons are allowed to import whatever they want even if it is at the expence of the local producer. Why import from New Zealand and Australia when there is a flush of local lambs? To ease the market the UK has exported lambs, I understand some have found their way to Europe, which has caused all sorts of problems in the EU, some have also found their way to China – which is interesting.

There is a sense of the unreal in international trade in food; remember the EU pays farmers about US$100 billion a year to keep them on the land and producing and at the same time, probably something as stupid as an FTA or similar, encourages the policy to be undermined with ‘cheap’ imports from countries like New Zealand.

To back up my friend’s story, the following week UK sheep farmers withheld lambs from the market. As we all know you can only do that for so long or they get too big or too fat or they lose their teeth and then for some reason only known to the buyers and not the consumers, their value goes down. I understand the logic about teeth at my age – but not when it comes to young sheep. Just another way to screw the producer?

This poster, (above) designed by the UK, NFU, appeared last week on the Sustainable Restaurant Association’s website in the UK. Strange bedfellows? I don’t believe so; I think the support of the restaurateurs is a sign of solidarity behind the UK farmer’s campaign for better prices and ‘Buy British’ and is to be commended. They supported their views with this editorial:

When farmers sell lamb at market they receive around £1.36 per kg,(A$2.90. 28kg DCW = A$81) losing £30 (A$63) on each lamb, but when it reaches the supermarket shelves, shoppers are charged up to ten times that amount. Global lamb prices have fallen in the last year, on the back of the strengthening pound and cheap imports from New Zealand.

The same restaurateurs also ran the milk ad, ‘Udder Madness’ in their newsletter.

It’s all here in an ABC interview with a British farmer

Australia is not immune from the milk price crash – It’s Global.

The worst of the current crash in milk prices has not been felt in Australia because our export market is more diverse than that of New Zealand where they have chased export gold with a few products like powdered milk and baby formula. There are however, many dairy farmers in Australia who maintain that their costs exceed their returns.

Nevertheless, those of us who still follow agriculture, which means very few ‘rural’ politicians, know that one dollar a litre retail price for milk here in Australia brought on an extreme, unwanted and undeserved catharsis, a purging of experience, skill, knowledge and dedication in our own milk industry–as I understood it at the time and it may well still be going on for all I know, but the drop in price at the farm gate, caused by the supermarkets, forced dairy farmers and their families to the wall and out of business, especially the smaller family farms. Far too many unable to manage the stress, took their own lives.

As we proceed I want you to remember that the majority of dairy farmers who went out of business were the smaller farms. At the end of this story you are in for a surprise.

World Wide Grain Prices are going Down – Or are they?

It was reported last week that Egypt had accepted a tender for wheat at less than US$200 tonne delivered Egypt. The tenders varied just above US180 tonne ex Ukraine. That sale would have sent a shiver down the spine of many a wheat grower in Australia. That is equivalent in Australian dollars today at about A$266 delivered Egypt. Ukraine is desperate for sales and foreign currency, but there is also an emerging glut of grain in the world.

I just read of wheat yields in Britain of 12 tonnes per hectare which has put that country on track for a second record harvest year. There is a serious a shortage of storage space and as a consequence a prediction that prices will fall on the international markets as that country looks for markets. Algeria springs to mind following their bad year.

The USDA has just put the cat among the proverbial grain price pigeons by reviewing upwards their harvest across all grains. Canola took a tumble in sympathy.

It’s hard to be a grain price optimist right now about 8 weeks away from the start of harvest in Western Australia. Usually, as the Australian dollar falls the better it is for those selling wheat. That needs the United States dollar to remain stable but that hasn’t happened because of the devaluation, twice in 36 hours, of the Chinese Yuan. This almost unprecedented move has has put commodity markets into turmoil because, again China, is a major importer of soy from America and, to make matters more interesting, Ukraine has just announced that they have already, in 2015, exported 800,000 tonnes of wheat to China. If that deal was done at the same price as the deal with Egypt, then grain markets could be in for a rough ride for a while.

China has been a significant importer of soy and wheat and they tell us they will soon be an importer of thousands, hundreds of thousands of live cattle from Australia. Our recent history of beef exports to China (~150000tonnes) is to say the least remarkable. The difficulty I have is that I cannot find anywhere at what price those sales have been made. The rumour is, and that’s all it is, is a rumour, that the sales have been of off-cuts and offal, products often difficult to place at any value in other markets. It’s a story for another day but the beef to China propaganda story, I think, leaks like a sieve. For one thing we don’t have the cattle in the blue tongue free zone and a herd build up will take a long time.

As a result of the Chinese currency devaluation will there be a currency war? Will other countries tightly tied to China like Viet Nam, Thailand and Cambodia also devalue? If they do what will that mean to exports? So many unanswered questions.

What does all this uncertainty mean for Food Security?

For some time and with many words, as is my wont, I have repeated the question raised by others. ‘How will the world feed 9 billion people in 2050?’ Some have predicted that the world will have to increase food production by at least 50% – some say more – perhaps according to the FAO, even 70% or more?

The greater challenge according to some, including the late Nobel Laureate Prof Norman Borlaug, is that 80% of that increase will have to come from what we call the Developed world– that means America, the EU, Australia and those other countries who consider themselves to be Developed.

That means the ‘Developing world’, will continue to develop. (no I don’t know when or how countries move from Developing to Developed, it’s most probably decided by those who consider themselves to be Developed.)

I commend an FAO publication World Agriculture towards 2030/2050 update 2012. by Nikos Alexandratos and Jelle Bruinsma who are members of the Global Perspective Studies Team at the FAO in Rome. It is a scholarly, sensible, extensive and thorough thesis on how the world will fare for food in 2050 and beyond. It is a refreshingly absorbing and relatively easy read and not difficult, even for me, to understand.

To write a summary of the paper would for me be impossible – and somewhat presumptuous. Suffice to say that the authors believe as a result of their extensive studies that 9 billion people in 2050 can quite easily be fed. A bit like today, not so much a shortage of food but getting the food to where it is wanted, particularly to sub-Sahara Africa, will be the challenge.

Of course they make assumptions, the most serious for us is that crop yields will continue to increase, albeit at a slower rate than the last forty years or so, ours are going down and we are reducing our plant breeding R&D. Someone has convinced the politicians that the North of Australia is going to save Australian agriculture. Only those who have never lived there would believe that.

Perhaps it was not part of their brief, but the only gaping hole that I could find in the report was the lack of any mention of money. Who is going to pay whom for what?

We have just had a look at the EU, one of the most agriculturally productive parts of the world, exporting, importing and moving within its own boundaries vast quantities of food – yet the very people who are growing that food are demonstrating because, in spite of massive subsidies, some US$100 billion a year, their costs are bigger than their returns and farmers are going broke.

Just to confuse us all, Colin Todhunter, a British journalist living in India, has challenged our agricultural system and that of the many ‘Developed’ countries in the world, he challenges those who manage huge funds and who travel the world buying vast tracts of land anywhere they can get their hands on them.

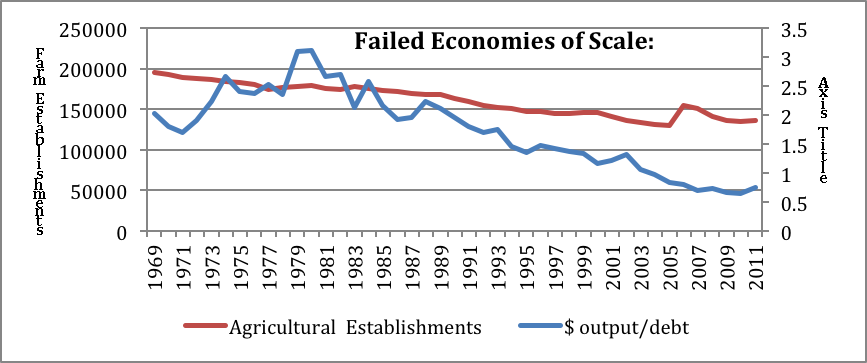

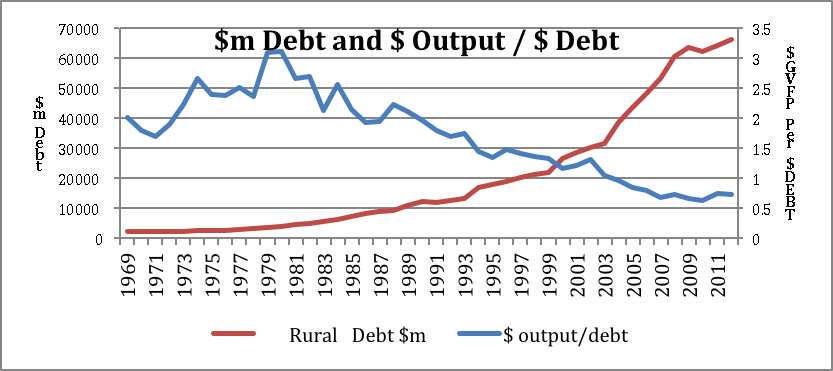

The following few graphs from Ben Rees will remind you that we might have got it wrong in Australia when it comes to farm size, debt, terms of trade and productivity within our system.

If you go back into the archive of Global Farmer to an early article, ‘Self Inflicted Injury’, I show how in Western Australia land prices, I won’t say values, prices, escalated in the 80s and accelerated into the 90s and continued until the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) put a brake what can only be called irresponsible and sometimes downright hair-brained borrowing and lending. Prior to the GFC the rapid increases in equity-financed farm aggregation caused neighbour to outbid neighbour for more land. ‘Get big or get out’ yet again The problem was production per hectare did not increase as land prices increased — but the land had to be paid for. Yields per hectare peaked in the 90s, costs were increasing, so the terms of trade were shot to pieces and the real value of wheat was static, even declining and actual values (of wheat) were historically poor.

Before the GFC the market was full of willing borrowers and more than willing lenders. The records speak for themselves, bank managers, farm consultant and accountants were all complicit in the deals that were done. I only make that remark on the assumption that someone, surely, must have produced a budget to justify every deal. How they did it, I don’t know.

Fig 1 shows what happened, as the number of farms and so the number of farmers and managers declined so too did the ratio of output to debt. Fig 2 shows that the gross value of farm production fell as the debt increased. Rural debt reached a peak in about 2013 at ~$64 billion, probably caused by the decrease in land values and the dramatic increase in the number of farmers who discovered that their debt to equity ratio was not where they or their banks wanted it. There were also far too many forced sales, for many the get big or get out didn’t work. There have been some spectacular farm business failures involving tens of millions of borrowed money.

See what I mean? Now look at this, written in October last year by Colin Todhunter he is not writing about Australia, but if the cap fits we have to wear it:

Small farms under threat.

The world is fast losing small farms and farmers through the concentration of land in the hands of the rich and powerful.

“The 2014 World Food Day theme – Family Farming: “Feeding the world, caring for the earth” – has been chosen to raise the profile of family farming and smallholder farmers. It focuses world attention on the significant role of family farming in eradicating hunger and poverty, providing food security and nutrition, improving livelihoods, managing natural resources, protecting the environment, and achieving sustainable development, in particular in rural areas.” [1]

Family farming should be celebrated because it really does feed the world. This claim is supported by a 2014 report by GRAIN, which revealed that small farms produce most of the world’s food [2].

Around 56% of Russia ‘s agricultural output comes from family farms which occupy less than 9% of arable land. These farms produce 90% of the country’s potatoes, 83% of its vegetables, 55% of its of milk, 39% of its meat and 22% of its cereals [3].

In Brazil, 84% of farms are small and control 24% of the land, yet they produce: 87% of cassava, 69% of beans, 67% of goat milk, 59% of pork, 58% of cow milk, 50% of chickens, 46% of maize, 38% of coffee, 33.8% of rice and 30% of cattle [4].

In Cuba, with 27% of the land, small farmers produce: 98% of fruits, 95% of beans, 80% of maize, 75% of pork, 65% of vegetables, 55% of cow milk, 55% of cattle and 35% of rice [5].

In Ukraine, small farmers operate 16% of agricultural land, but provide 55% of agricultural output, including: 97% of potatoes, 97% of honey, 88% of vegetables, 83% of fruits and berries and 80% of milk [6].

Similar impressive figures are available for Chile, Hungary, Belarus, Romania, Kenya, El Salvador and many other countries.

The evidence shows that small peasant/family farms are the bedrock of global food production. The bad news is that they are squeezed onto less than a quarter of the world’s farmland and such land is under threat. The world is fast losing farms and farmers through the concentration of land into the hands of the rich and powerful.

The report by GRAIN also revealed that small farmers are often much more productive than large corporate farms, despite the latter’s access to various expensive technologies. For example, if all of Kenya’s farms matched the output of its small farms, the nation’s agricultural productivity would double. In Central America, it would nearly triple. In Russia, it would be six fold.

Yet in many places, small farmers are being criminalised, taken to court and even made to disappear when it comes to the struggle for land. They are constantly exposed to systematic expulsion from their land by foreign corporations [7], some of which are fronted by fraudulent individuals who specialise in corrupt deals and practices to rake in enormous profits to the detriment of small farmers and food production [8].

Imagine what small farmers could achieve if they had access to more land and could work in a supportive policy environment, rather than under the siege conditions they too often face. For example, the vast majority of farms in Zimbabwe belong to smallholders and their average farm size has increased as a result of the Fast Track Land Reform Programme. Small farmers in the country now produce over 90% of diverse agricultural food crops, while they only provided 60 to 70% of the national food before land redistribution.

Throughout much of the world, however, agricultural land is being taken over by large corporations. GRAIN concludes that, in the last 50 years, 140 million hectares – well more than all the farmland in China – have been taken over for soybean, oil palm, rapeseed and sugar cane alone.

By definition, peasant agriculture prioritises food production for local and national markets as well as for farmers’ own families. Big agritech corporations take over scarce fertile land and prioritise commodities or export crops for profit and markets far away that cater for the needs of the affluent. This process impoverishes local communities and brings about food insecurity. The concentration of fertile agricultural land in fewer and fewer hands is therefore directly related to the increasing number of people going hungry every day and is undermining global food security.

The issue of land ownership was also picked up on by another report this year. A report by the Oakland Institute stated that the first years of the 21st century will be remembered for a global land rush of nearly unprecedented scale [9]. An estimated 500 million acres, an area eight times the size of Britain , was reported bought or leased across the developing world between 2000 and 2011, often at the expense of local food security and land rights.

A new generation of institutional investors, including hedge funds, private equity, pension funds and university endowments, is eager to capitalise on global farmland as a new and highly desirable asset class. Financial returns, not food security, are what matter. In the US, for instance, with rising interest from investors and surging land prices, giant pension funds are committing billions to buy agricultural land.

The Oakland Institute argues that the US could experience an unprecedented crisis of retiring farmers over the next 20 years, leading to ample opportunities for these actors to expand their holdings as an estimated 400 million acres changes generational hands.

The corporate consolidation of agriculture is happening as much in Iowa and California as it is in the Philippines, Mozambique and not least in Ukraine.

As indicated earlier in this piece, Ukraine’s small farmers are thriving in terms of delivering impressive outputs, despite being squeezed onto just 16% of arable land. But the US-backed toppling of that country’s government may change all that. Indeed, part of the reason behind destabilizing Ukraine was for US agritech concerns like Monsanto to gain access to its agriculture sector, which is what we are now witnessing.

Current ‘aid’ packages, contingent on austerity reforms, will have a devastating impact on Ukrainians’ standard of living and increase poverty in the country [10]. Reforms mandated by the EU-backed loan include agricultural deregulation that is intended to benefit agribusiness corporations. Natural resource and land policy shifts are intended to facilitate the foreign corporate takeover of enormous tracts of land. The EU Association Agreement also includes a clause requiring both parties to cooperate to extend the use of biotechnology. Frederic Mousseau, Policy Director of the Oakland Institute states:

“Their (World Bank and IMF) intent is blatant: to open up foreign markets to Western corporations… The high stakes around control of Ukraine’s vast agricultural sector, the world’s third largest exporter of corn and fifth largest exporter of wheat, constitute an oft-overlooked critical factor. In recent years, foreign corporations have acquired more than 1.6 million hectares of Ukrainian land.”

As World Food Day approaches in celebration of the role of the family farm in feeding the world, from India to Ukraine powerful US agritech corporations continue to colonise agriculture and undermine the continued existence of small farms. This is achieved by various means, including militarism, ‘free’ trade agreements, commodity market price manipulations, loan/aid packages, the co-optation of political leaders and the hijack of strategic policy-making bodies. As a result, food security and local/regional food sovereignty is being threatened.

Notes

1] http://www.fao.org/world-food-day/home/en/

2] http://www.grain.org/article/entries/4929-hungry-for-land-small-farmers-feed-the-world-with-less-than-a-quarter-of-all-farmland

3] Russian Federation Federal State Statistics Service, Russia in Figures 2011.

4] Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estadistica, “Censo Agropecuario 2006”,http://tinyurl.com/m376s82

5] Braulio Machin Sosa et al., ANAP-Via Campesina, “Revolución agroecológica, resumen ejecutivo”

6] State Statistics Service of Ukraine. “Main agricultural characteristics of households in rural areas in 2011”

7]http://www.theecologist.org/News/news_analysis/2267255/gm_crops_are_driving_genocide_and_ecocide_keep_them_out_of_the_eu.html

8] http://www.grain.org/article/entries/5048-feeding-the-1-percent

9] http://www.oaklandinstitute.org/sites/oaklandinstitute.org/files/OI_Report_Down_on_the_Farm.pdf

10] http://www.oaklandinstitute.org/walking-west-side-world-bank-and-imf-ukraine-conflict

Posted 11th October 2014 by Colin Todhunter

I have followed some of that EU trade and the US enforced Russian sanctions commentary since the early days of the conflict as well as closely watching EU discussions re the TTIP, TPP & TiSA. What worries me is the gung ho attitude of trying to finalise trade deals without reviewing the very old CBA or modelling and the willingness to use all forms of propaganda as well as slander to convince the public that the deals must be supported at all costs, why? Anyone who has ever run a business knows there is the right time, wrong time, as well as place, and those that attempt to force their way in can be mercilessly dudded. I see a number are attempting to have the EU-Aus finalised now, as well as our complete alignment with EU ISO standards. I don’t know enough to know how much that could hurt but knowing that the EU has the largest ETS and some of those standards have supply chain GHG emissions as well as animal welfare tracking I do wonder about the cost impacts in such a large nation as Aus.

Subsidised asian trade, I wonder if they would also fall into our basket of aid for trade nations, then they would truly be getting a free ride to compete against some of the least subsidised farmers on the planet.