The Story so Far.

The question that should be asked is whether large swathes of wheat growing land in Australia and particularly in Western Australia will be viable in the future? Because if the answer is no, then now is the time to start looking at the ways and the means for restructuring Australia’s wheat belt.

The question that should be asked is whether large swathes of wheat growing land in Australia and particularly in Western Australia will be viable in the future? Because if the answer is no, then now is the time to start looking at the ways and the means for restructuring Australia’s wheat belt.

There are two conflicting forces at work. Two opinions based on two areas of science:

1. Soil amelioration is becoming popular in Western Australia in an effort to improve crop yields. It is expensive, in some cases very expensive. There are yield gains to be had, how long the gains last is open for debate because they vary site by site. There are also problems particularly with soil stability and structure.

2. Climate scientists are predicting falls in crop yields in Western Australia over the next twenty years to levels which I predict will make it uneconomic to grow wheat given the year on year rise in costs and the decline in the real price of wheat over the last fifty years.

The Backstory.

In March 2018 I wrote in the Global Farmer there will be no Australian wheat industry in 20 years:

A recent article in ‘The Conversation’ predicts that even if wheat farmers get a lot closer to the ‘potential yield’ than they are today, by 2041 the national average yield will be 1.55 tonnes per hectare, down from where they say it is at present at 1.74 tonnes per hectare.

Yields will never get that low, given that nothing dramatic and unexpected happens like new high yielding drought tolerant wheat varieties, the wheat industry as we know it will be finished long before we get to 1.55 tonnes per hectare, that’s back to the yield of the 70s with the costs of 2041.

It was self evident in that article that getting bigger by buying another farm was not working for the majority — nothing has changed. Rural debt continues to increase at the rate of about a billion dollars a year, and the statistics show there is no economy to be made by borrowing more and scaling up of the operation, the dictum of ‘get big or get out’ has been proven to be wrong.

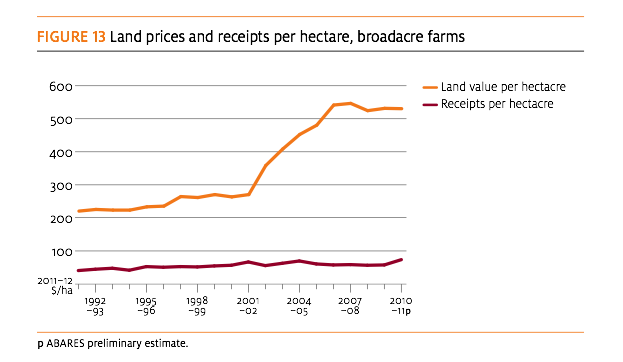

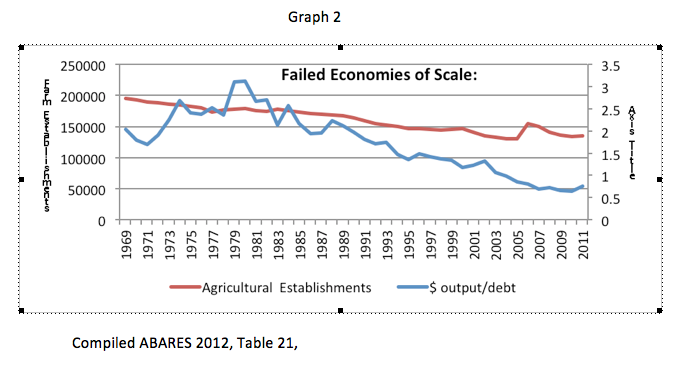

To just get out and capitalise on rising land values may well have been a better decision for many, see figure 13 — and then see the effect on productivity caused by getting bigger, Graph 2, the evidence is that farming more land coupled with the purchase of bigger machinery etc is driving productivity down:

Nothing has really changed since these figures were compiled nine years ago. The trend towards farm aggregation has continued, so the number of farming establishments is still declining as they continue to get bigger the real challenge is that productivity growth in broad acre farming from the seventies to the twenty twenties has been just 1% per year and for all agriculture it is declining. If the real estate agents are to be believed the price of land continues to increase.

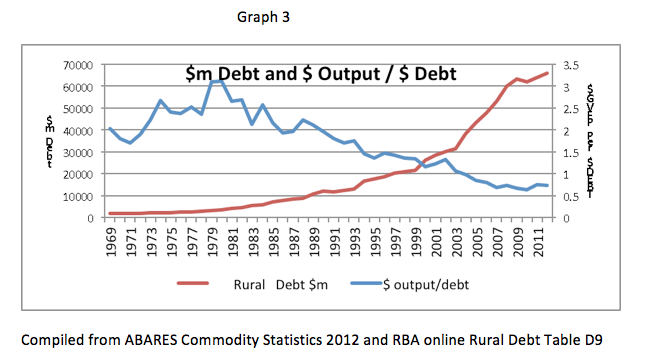

The real worry is the rural debt. Everybody except me and Ben Rees don’t seem to think there is a problem. I sometimes wonder if those who don’t worry about debt are aware how many dollars, a dollar of debt has earned over time?

Many boast about the equity they hold in their farm(s). Equity is the difference between value and debt. Value is based on opinion and the market. Graph 2 and 3 challenge the merit of rising land values.

The right axis is the dollar value gross value of farm production per dollar of debt. So, in 2008-9 one dollar of debt supported seventy cents of production the figure for 2020 is one dollar of debt supports about sixty cents of production, compare that to 1979 and then to 1999 where it was dollar for dollar borrowed. Rural debt is now about $80.5 billion and increasing at about one billion a year and production is almost static in cereal production and declining in Australian agriculture overall.

The right axis is the dollar value gross value of farm production per dollar of debt. So, in 2008-9 one dollar of debt supported seventy cents of production the figure for 2020 is one dollar of debt supports about sixty cents of production, compare that to 1979 and then to 1999 where it was dollar for dollar borrowed. Rural debt is now about $80.5 billion and increasing at about one billion a year and production is almost static in cereal production and declining in Australian agriculture overall.

The question must be asked who is advising the farmers to borrow more and more based on these numbers? How long can the debts continue to increase and for how long will farmers borrow to support declining productivity?

Now it is 2020. Is there a Catch 22?

The Grains Research and Development Corporation – Western News of June 2020, contains a YouTube-Skype conference between growers and their advisers as they share stories of the damage they suffered in the Geraldton region and in the eastern wheat belt from a wind erosion event in May 2020. They are joined by a grower from the South Stirlings on the south coast who related his experience from similar wind events a couple of years ago, for me that was a blast from the past, look at page 211.

I was in a time warp as I watched and listened. Back in the 70s our crops often suffered badly from wind erosion and it was all to do with the way we managed our land.

The common practice in those days was to burn bare the paddocks to be cropped — wait for the opening rains then plow or scarify.

Then, when the weeds germinated cultivate to kill them, sometimes two or three cultivations were needed. Then we would seed with a spring-tined seeder (combine) often pulling a set of harrows just to give the weeds another tickle. The result was a good seed bed and often plenty of weeds. Later this practice became known as ‘recreational tillage’.

In the late 70s a few of us started direct drilling and reduced the amount of stubble burning to what we called ‘cold burns’. The reduction in burning and a one pass sowing operation with a combine improved the organic matter and the water stable aggregates in the soil and wind erosion decreased — the change was that dramatic.

Most crop farmers claim these days that they practice no-till, which in fact is just an evolution of what was started 50 years ago. In reality little has changed apart from the size and weight of the machinery in the paddock and in many cases the resultant increase in soil compaction.

I have also been surprised at the high level of soil disturbance caused by the design of some of the ‘new’ wide seeders and the speed at which they travel through the soil. High speed soil disturbance has always been the enemy of surface soil structure.

Many claim to be the father of no-till. Over the years some farmers and scientists have been awarded medals and received honours for being the pioneers of no-till, when if truth be known they were late adopters.

For the real history of Direct Drilling in Australia there is now an archive at the National Library of Australia where all the facts and figures can be found. It is an oral history in the main, one-on-one interviews with the farmers and scientists who were practicing and researching tillage reduction at the very beginning and there aren’t many of us left after more than fifty years. This is real Australian agricultural history.

Whether any of the knowledge and experience the of research done in the 70s, 80s and 90s has been passed down through the generations I don’t know. It would seem, listening to the farmers on the tape, that the current generation are hell bent repeating the experiences (sins) of their forefathers when it comes to soil management.

It beggars belief that the practice of reducing soil disturbance to build the structure of our ancient soils so that they stand some chance of supporting continuous cropping programmes, can be forgotten when it starts to become apparent that those same soils cannot support profitable continuous cropping without resorting to massive disturbance both on the surface and beneath the surface, and in some cases going back to mold board plowing, which is the Parthenon of recreational tillage. Turning back the clock on the improvements made in soil structure and health over the last fifty or so years, is brave to say the least.

Back in the Good Old Days of Wheat and Sheep.

To tell this story properly I have to go back to another age, back to the 1970s 80s and 90s. Back in those times what we now call the wheat belt was in fact the wheat and sheep belt. We also need to recognise that the rainfall pattern for the agricultural region of Western Australia has changed since that time and that change has had an effect on crop growing.

There is less rain to start with, and seasonal rainfall patterns have changed slightly — there is more rain now during the summer non-growing months and less in the growing season between say May to late September early October. And the famous ‘break’ to the season is now less predictable than it was. There was a time when the ‘break’ was almost guaranteed to arrive in the last two weeks of May and seeding was never started before those opening rains.

Now seeding seems to be a matter of the time of year rather than the seasonal condition. Dry seeding is common as is the complexity and cost of chemicals to control weeds and other pests.

Personally, I disagree with the Department’s view of what they call the consequences of climate change — there is no proof that we now receive more cyclones and the fires are worse etc., But they are right about rainfall patterns.

The sheep and wool industry collapsed in Australia in the early 90s when there were about 36 million sheep in WA — there are now about 14 million (7-8m breeding ewes) and the national flock has shrunk from a peak in 1987 0f 163 million to about 63 million in 2020/21. The decline in the sheep flock is forecast to continue.

The rapid contraction of 100 million sheep (and wool) was replaced by 4.2 million cattle, one can assume this increase was mainly in the higher rainfall areas, farmers in what had been the wheat and sheep areas increased the size of their cropping enterprises.

In the nine years between 2000 t0 2019 Agricultural production in Australia increased in value by about $10 billion. Livestock prices especially cattle improved but grain prices declined. As growers moved from sheep and wheat into all grain production they were forced into the purchase of bigger more sophisticated and expensive machinery to manage a bigger crop area with fewer people.

It is a sobering fact that Australian wheat yield improvements over the last 50 years fall far below those of our main competitors in the export wheat market, a market vital to West Australian farmers. Costs rise every year and yield and prices are static. It is almost impossible to find growers or their advisers who will admit to only producing the national average wheat yield, but the average is there and it is undeniable.

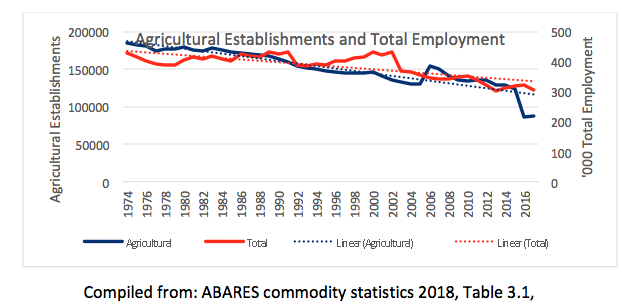

So, the biggest changes in Australian agriculture in the last fifty years have been structural. The number of farms has declined quite dramatically. In 1970 there were about 14,000 farms in the wheat belt of Western Australia, today there are less than 5,000, a decrease of over 60%. This structural change has happened all over Australia as Graph 1 shows:

Graph 1.

Graph 1 provides empirical evidence of policy outcomes after four decades of rural adjustment. The critical variables analysed are: farm establishments and rural employment. According to ABARES commodity statistics, in 1977, there were 173,625 agricultural establishments. By 2017, Australia’s number of farm establishments had fallen 49.3% to 88,073 . Over the same period rural employment contracted from 414,000 to 329 000 or 20.5%. The policy direction of rural adjustment maintained over four decades effectively removed 49% of farm establishments and 20.5% of total employment in rural Australia. The loss of farm enterprises and employment would flow on to impact negatively upon regional population and stability. Ben Rees. benrees.com.au

Graph 1 provides empirical evidence of policy outcomes after four decades of rural adjustment. The critical variables analysed are: farm establishments and rural employment. According to ABARES commodity statistics, in 1977, there were 173,625 agricultural establishments. By 2017, Australia’s number of farm establishments had fallen 49.3% to 88,073 . Over the same period rural employment contracted from 414,000 to 329 000 or 20.5%. The policy direction of rural adjustment maintained over four decades effectively removed 49% of farm establishments and 20.5% of total employment in rural Australia. The loss of farm enterprises and employment would flow on to impact negatively upon regional population and stability. Ben Rees. benrees.com.au

Many ‘wheatbelt’ towns in Western Australia and around the country are now struggling to remain viable. Transient labour, mainly international backpackers have replaced married couples on farms. Shearers have found another profession and that has driven them to their regional centres or to the big city. In every country town shops are vacant, vehicle and farm machinery dealers yards are empty, schools are struggling for pupils and town centres are starting to look tired and a little uncared for.

It is sad to see once thriving communities besieged in this way— this change begs the question whether rural Australia is experiencing social progress or regression and will the trend continue and if it does, what will happen, because the average age of farmers is now 58 (77% male with 35 years experience)and it slowly increases every year — sooner than we think many will be physically unable to farm.

The Loss of 100 million sheep and Continuous Cropping.

The other major change that has been brought about by the loss of over 100 million sheep, is the adoption of almost continuous cropping on many farms. In my view this has been a brave move when we consider the age and the fragility of many Australian soils.

It was not until the advent of persistent clovers, particularly sub-clovers that a good and sustainable rotation was achieved on West Australian wheatbelt soils. A good clover rotation was seen as being the cornerstone to good crop farming. Several years of a good clover ley or pasture, well stocked with sheep certainly made for a simple cropping programme.

The loss of 100 million sheep must have had an effect on the structure and the fertility of many wheat belt soils. We no longer have dung beetles burying the thousands of tonnes of sheep dung every year. That simple process must have had a beneficial effect on the soil biota and consequently on crop yields.

Many of us who cleared land can remember some of the outstanding early crops grown on land which in its virgin state carried acacias (wattles) which are leguminous plants. That we successfully destroyed the natural biota by clearing and cultivating and then rediscovered it with clovers is now a matter of history.

The beneficial effect of sheep on the soil must be balanced by the damage that sheep can cause by overgrazing where thousands of little hooves will break up the surface and make it subject to wind and water erosion. Dept Researcher Brian Marsh in the 80s measured ‘sheep stable aggregates’.

We have already seen that wheat yields in Australia have only increased marginally since the sixties when we cropped with just super phosphates (zinc, moly, copper etc.,) and the free nitrogen from the clover pasture phase. Have the marginal yield increases since that time justified the increase in all costs, including machinery?

Australia has not managed to break the 2 tonnes of wheat per hectare barrier for as long as I have been in agriculture and that is over 60 years. In the 70s the average was about 1 tonne per hectare, yields improved through to the 90s and after that they have largely plateaued and now sit, depending on whose figures you use, between 1,7 and 1,9 tonnes per hectare.

That failure to improve yields is in spite of all the millions of dollars of growers levies that have been given to the GRDC and the millions which have been given by state and federal governments to universities and Departments of Agriculture to stimulate agronomic research to improve wheat yields and reduce costs.

Soil Amelioration.

The practice of soil amelioration is as old as agriculture itself. In Britain there was a practice called ‘marling’ which dates back to the 14th Century. Calcium carbonate, lime, and chalk were mixed with heavy clay soils to improve soil structure and so fertility. Labor intensive in the days of horse and cart and shovel, but proven to be beneficial to the soil and the effect lasted for many years.

The Dutch famously reclaimed land from the sea and slowly brought it into production. Some areas in Holland are seven metres below sea level.

There is a mass of information regarding the various types of soil amelioration in Australia from deep ripping to getting out the old disc plow or buying a moldboard plow for soil inversion and for burying herbicide resistant weed seeds and for bringing up sub soil. Or using a rotary hoe or spader to dig up the subsoil and mix clay, lime and gypsum in with the top soil. All what my generation called maximum tillage.

There is a very good paper on soil amelioration and the costs and the benefits and there certainly are some big costs and some short to medium term benefits, there are also some major dangers like erosion both from wind and water, loss of carbon or soil structure and so on.

Given the economics of growing wheat at present the money for amelioration will most likely have to come from increased borrowings. The final paragraph in the paper Soil Constraints: ‘A Role for Strategic Deep Tillage’ sums up the situation:

Amelioration of soil constraints can, in part, enable a reduction in the gap between current and potential water limited grain yields but capturing and sustaining this benefit will require the simultaneous implementation of a range of management strategies to reduce the range of abiotic and biotic constraints that limit grains productivity. (abiotic = physical. biotic = organisms)

Is this the Catch 22 for wheat growers?

The simple truth is that wheat yields and prices are not improving at a rate sufficient to offset the rise in costs or to make the Australian wheat industry competitive with Ukraine and others in the export markets.

Soil amelioration is one strategy being employed by wheat growers in an attempt to improve their financial position and ensure their business remains tenable.

If those measures work are they going to be offset by something which is out of the control of the wheat grower — climate change? Is this the big catch 22?

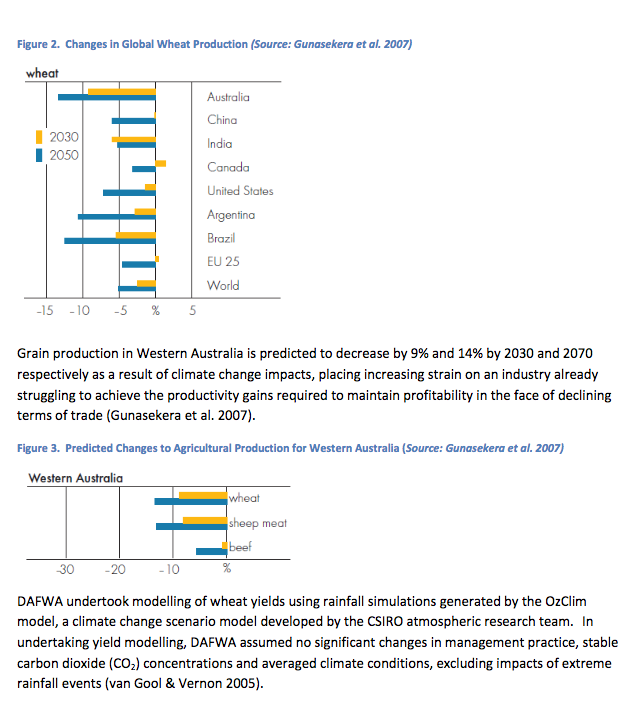

The Wheat Belt NRM has produced a paper Climate Change pdf It is a predictive document based on theirs and others research in 2013; they tell us what we can expect to happen to grain yields around the world, in Australia and in WA. It’s an interesting article, it’s not all good news but decision making is not supposed to be easy. It gets easier the more you know. I have reproduced some of their maps and graphs and commend the article to you with the comment that if the predictions are true, the wheat belt of Western Australia is on its way back to range-land farming within the next twenty years. Later on compare what Gunesekara et al are predicting with the opinion of scientists from the CSIRO.

These scientists claim that the effect of climate change on world wheat production will be decline over time in many countries and particularly in Australia:

These scientists claim that the effect of climate change on world wheat production will be decline over time in many countries and particularly in Australia: It’s not all bad news.

It’s not all bad news.

There are other statistics however to gladden the heart of wheat growers. Data collected by Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre (AEGIC) shows that grain growers all around the country are producing more grain with less rain. According to Dr David Stephens. AEGIC agro-meteorologist, Australian grain growers, according to a national study, are up to twice as water efficient as they were 30 years ago,

In an ABC interview Dr Stephens. relates that a comprehensive data map compiled between 1982 and 2012 shows that many wheat growing regions have improved their water use efficiency between 50 and 100 per cent.

Dr Stephens said grain farmers were really “pushing the boundaries” of yield production and water efficiency in terms of adapting to decreasing rainfall.

Dr Stephens. also talks about the efficiency improvements that farmers have made with time of planting and a raft of inputs which have helped them become more water efficient in their crop growing.

Gazing into the Crystal Ball.

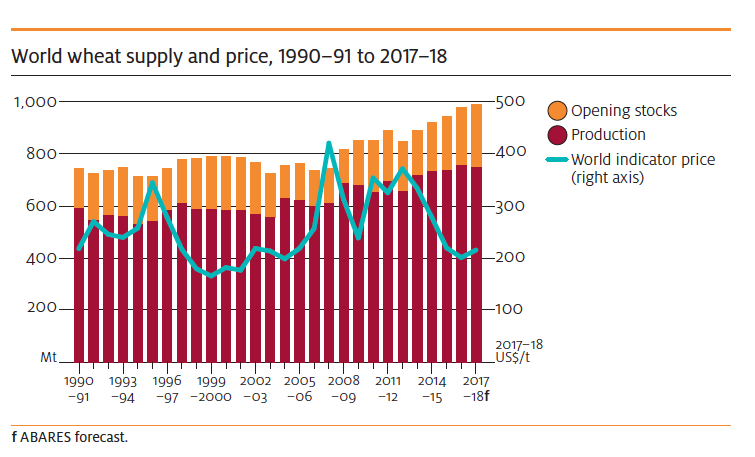

If the scientists are right it looks like there will be big change for wheat farmers in Australia over the next twenty years — they will have to continue to be optimists when it comes to price and yield if they make the brave decision to continue growing wheat. The full horror of wheat prices since 2012 is evident in GRAPH 4 and the big question is whether a static price and a falling yield potential in the future can keep wheat farming viable?

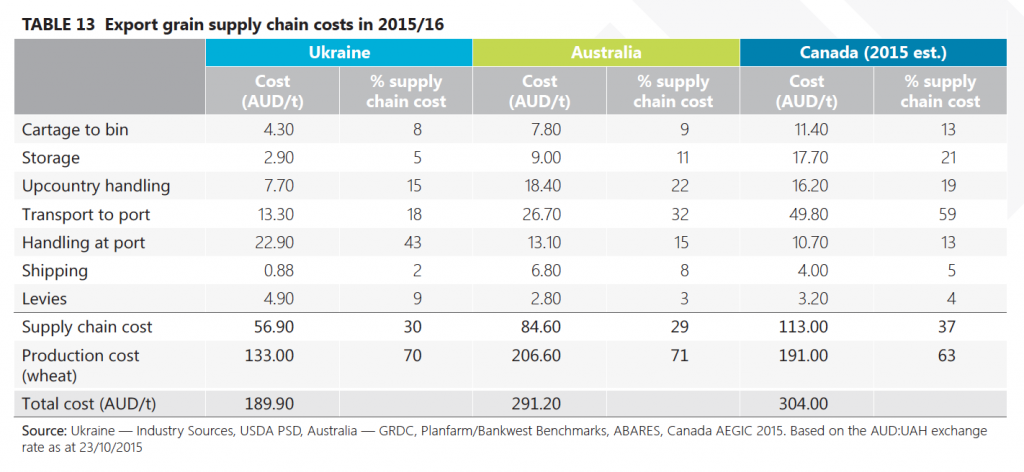

According to figures compiled by Australian Grains Export Innovation Centre (AEGIC) report on the Ukraine Supply Chain, for 2015/16 there is a supply chain cost in Australia of $84.60 per tonne and a production cost of $206.60 per tonne, making a total cost to grow of of $291.20. per tonne nearly $100/tonne more than costs in Ukraine.

It is impossible to predict the future, we know this to be true as we all experience strange time in the year of the pandemic.

It is impossible to predict the future, we know this to be true as we all experience strange time in the year of the pandemic.

Nevertheless it would be foolish to ignore what some of the best brains in the wheat industry are saying and there is no denying that the real value of wheat has been declining for well over 60 years and it would be a brave person who predicts that costs to grow wheat will decline over twenty years or that labour will become easier to find.

There is a strong argument for a superior, more commercially and financially aware leadership in agriculture in Australia and particularly Western Australia, where wheat growing is now the dominant enterprise and which provides the bulk of Australia’s export grain.

When not if wheat growing becomes unviable in parts of Western Australia it will start in the east and the north eastern areas particularly north of Three Springs, but really no area it would seem from the climate science can remain viable unless something dramatic happens to improve yields, costs and prices received and that trifecta seems unlikely in the extreme.

So what will happen to these areas in the lifetime of our children and grandchildren? Are there other crops that can be grown for which there is a market, if there are I cannot think of them.

The obvious answer is that as the world markets become more sophisticated and wealthy so there will be a demand for animal protein.

Whether the world will be able to manage without natural fibres in the future remains a serious question. If the world reduces the amount of oil it produces it will reduce the amount of synthetic fibre it can produce. If there is an increasing demand for wool then the merino may have a future but only if the challenge of shearing can be accomplished without the hard labour currently involved.

Keeping cattle would be less of a problem once suitable permanent pastures had been established. The same goes for goats and Australia should always remember that more goat meat is eaten in this world than sheep meat.

Whatever the outcome the uncertainty of the future for wheat growing in Western Australia is worthy of serious debate about restructuring agriculture as we know it — before it is too late.