In this issue I republish the simple truth from a leader in Australian grain marketing, Mr Palmquist from GrainCorp. He confronts us with the unpleasant reality that an antiquated infrastructure is being paid for by grain growers and I suppose by definition he is saying the only ones paying, are the growers. An expensive infrastructure, together with the poorest world wheat prices for more than a decade are wrecking the budgets of Australian wheat producers. This grain trader says he has no option but to pass the costs on to the grower — he would say that wouldn’t he? He only has to answer to shareholders — growers only have to answer to the bank. As an example he claims it’s cheaper to move grain from Ukraine to Indonesia than it is to move it 350 kilometers from Swan Hill to Geelong.

Why have we have let this situation develop to the point where we in Australia are so far behind world best practice? No wonder rural debt is increasing when growers have no option but to pay for the shortcoming of indolent governments. If private enterprise has to pay to upgrade the infrastructure, Mr Palmquist is claiming the growers will pay for it with lower prices. If growers costs exceed returns they will be forced to stop growing wheat, I suppose he knows that?

This example substantiates the figures generated by the Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre (AEGIC) which showed quite plainly, that it costs Australian growers nearly twice as much as Ukraine farmers to grow and get a tonne of wheat to port. Go back and have another look at the figures.

For your consideration, I republish the findings of two teams of highly qualified research scientists. Independent of each other they have concluded that even if growers continue to achieve substantial improvements in water use efficiency over the next 20 years or so, so in spite of what growers do, yields are going to continue to decline back to where they were in the 1980s at about 1.55 tonnes per hectare. I have concluded that the only thing that can save the wheat industry in Australia based on the evidence before us is a fairy godmother with a magic wand. A magic wand that can bring us high yielding drought tolerant wheat — when do we want them? Now. The GRDC should explain where the millions of dollars they have spent on research has gone and why there are no fairies with magic multi million dollar wands at the bottom of every levy paying wheat grower’s garden.

Why are we mute?

Why doesn’t agriculture have a political voice? Why are we mute? We have a federal minister for agriculture, lower house members from country electorates and senators who represent agricultural regions and to back up our politicians we have a vast federal agricultural bureaucracy of scientists, economists and for all I know, futurists. All of the foregoing is replicated in every state parliament and bureaucracy within the federation. There are thousands of people who live off agriculture and nobody mentions the problems facing the future of Australia’s $6 billion wheat industry in the places where decisions are made.

Does the Prime Minister know about the problems in the wheat industry? Does Barnaby? If they do why aren’t they talking to Australia’s biggest rural exporters? If they don’t know, why the hell not?

Is it any wonder the country is asking, is it time for change? Is it time for a big change? Rock the boat? Shake them up? Revolution? New thinking? There is an election coming up in WA and suddenly there are rivers of money where a few weeks ago there was none. ‘There are fairies at the bottom of our garden’ and they all smell of oak and pig meat.

I am not alone when it comes to questioning the viability of the international wheat industry. There is a link to a story in the prestigious Wall Street Journal (WSJ) later in this article. Kansas growers are despondent and talking about what would have been unthinkable a few years ago. The WSJ article drives home the rapid rate of change in the world and the price of transition. The challenge for Australian wheat growers is to determine what their place is in this world of constant change.

The problem I have is that I am just one voice and it doesn’t matter how many politicians and agri politicians receive the Global Farmer, and read the convincing evidence, nothing happens, nobody makes contact, I reckon everyone is frightened lest it be known that they know what the problems are and they may be called to account by growers.

When I use the plural pronoun ‘we’, I’m not really talking about ‘us’ am I? I’m really talking about governments. As far as I am aware neither the Federal Government or any of the State Governments have in their current budgets or in their forward estimates, funds earmarked to bring the grain handling infrastructure in this country up to a standard where it would be world competitive. Fiscal restraint is all we hear, so short of a rural revolution I don’t see anything changing and that is very bad news indeed. There is no money to spend on making Australia competitive and we need it because look at this:

The problem is already with us right now but nobody wants to talk about it.

Last year the boss of Grain Corp had this to say in the Financial Review.

GrainCorp chief executive Mark Palmquist said Australia’s natural freight advantage had been eroded by the plunging price of ocean tankers.

“What used to be a differentiator or advantage in Australia has disappeared,” Mr Palmquist told The Australian Financial Review.

He said the freight advantage was as much as $US15 per tonne. (emphasis added)

“We are losing market share in Asia. In the Middle East we are losing tremendous market share,” Mr Palmquist said.

To remain competitive grain traders, including GrainCorp, had to cut the price of wheat it pays farmers.

“It goes right back down to the farmer. That becomes a big issue,” he said.

He said it was about $5 per tonne cheaper to send wheat from the Ukraine to Indonesia than it was to transport grain for the 350km from its Swan Hill hub to Geelong.

“It [lower ocean freight] exposes Australia to its supply chain costs,” Mr Palmquist said. “We were insulated. Now we are exposed.”

The comment by Mr Palmquist drives a stake into the heart of our problem with our supply chain costs. He nails it, our system is too expensive, it is uncompetitive. Makes me wonder how good GrainCorp’s due diligence was when they among others were glad to see the back of AWB. Grain Corp must have known of the deficiencies in the infrastructure and I wonder who advised the federal government that it would not be in Australia’s interest to sell the company to Arthur Daniels?

Now America talks about the unbelievable.

In the last edition I published a letter from a wheat farmer in Colorado. It was a familiar tale — last year his costs were greater than his receipts. Now the story grows and it is national; it goes to the very heart of American grain farming. Never mind Donald Trump, here is a bit of what is going on now in the hearts and minds of American wheat farmers.

During this last week a colleague in America, followed by one in Australia, drew my attention to an article in the prestigious Wall Street Journal ‘The next American farm bust is upon us’.

I was pleased to see that the mainstream media (MSM) in the United States prepared devote the space to an article on agriculture, which told the truth about what is going on in their grain belt and questioning the future of America exporting grain. You did read that correctly and I haven’t made a mistake — if America is questioning whether it should be or can afford to be in the wheat export business, that could herald a shift in the tectonic plates of the world’s grain trade. Read the complete article because it’s not in the excerpt.

Reading the article for many grain farmers in Australia will be like reading their own life story and it reinforces the message I tried to give in the last article in the Global Farmer, that there are tough times ahead. Should we in Australia be asking the same question, can we afford to be in the international wheat trade? When costs often equal or exceed receipts — how often is too often?

Here are the opening paragraphs, I urge everyone to read the complete article. If the link asks you to join the WSJ, go back to your search engine and put in; ‘the next American farm bust is upon us’ you should find it then – it is there.

RANSOM, Kan.—The Farm Belt is hurtling toward a milestone: Soon there will be fewer than two million farms in America for the first time since pioneers moved westward after the Louisiana Purchase.

Across the heartland, a multiyear slump in prices for corn, wheat and other farm commodities brought on by a glut of grain world-wide is pushing many farmers further into debt. Some are shutting down, raising concerns that the next few years could bring the biggest wave of farm closures since the 1980s.

The U.S. share of the global grain market is less than half what it was in the 1970s. American farmers’ incomes will drop 9% in 2017, the Agriculture Department estimates, extending the steepest slide since the Great Depression into a fourth year.

“You keep pinching and pinching and pretty soon there’s nothing left to pinch,” said Craig Scott, a fifth-generation farmer in this Western Kansas town.

The grain infrastructure is worse than it was in the sixties —blame my generation.

It is evident to ‘blind’ Freddy’ that the infrastructure supporting agriculture in Australia is rubbish. I could write a book on the decay of our infrastructure over the last fifty years. Mark Palmquist from Grain Corp obviously doesn’t think much of it and the AEGIC laid it out in numbers in my last article.

When I came to Western Australia in the sixties, having been trained in British agriculture and having been witness to great change over there of the dawn of intensive agriculture, I remember the gasps of wonder in about 1965, when a wheat called I think, Prof Marchal, yielded 2 tons to the acre (~5 tonnes/hectare) when the UK average was just over 1 ton. We left behind cold weather, a Labour government and what was becoming an increasingly complicated agriculture for the sunshine of WA. We didn’t know really what to expect.

For my first harvest in Western Australia, I drove a Chamberlain Countryman pulling a Horwood Bagshaw pto header. We had two field bins and my oppo, Raymondo, drove the Ford 8 tonne truck with a Five-in-One bin loaded with just under 8 tonnes of grain to ‘the bin’ in Coorow. On a good day he got in five or six trips. We all know the system as it was, CBH received the grain, tested it and that was the last we saw of it. It went into the bin and was eventually transported by rail to either Geraldton or Kwinana.

At the end of or during harvest our boss filled in a few forms and he got paid enough to pay the bills and a bit left over, the rest I learned, backed by the federal government, would come as the grain was sold out of the ‘pool’. I got paid a bonus of wheat and in that way I became a wheat grower and a member of a pool.

I marvelled that wheat farmers in a country as big as Western Australia had developed through CBH, what to me at that time was and still is, the simplest and most efficient system I could think of for getting grain long distances (compared to the UK) from the country to the port and at the same time guaranteeing that everyone got paid.

The ‘system’ in those days depended 100% or just about, on the wonderful rail network that previous generations had built. Every bin and every town was connected to the rail which led to the ports. In the first 100 years of settlement, that is from 1829 to 1929 the government of WA and the Commonwealth constructed 7800 kilometers of rail. Looking at the map most of that rail was still operating in 1967.

It was my generation and those that followed who more than doubled the harvest between then and now.

It was my generation and those that followed who elected the governments of all persuasions who quite deliberately let the rail system rot.

It was my generation and those that followed who elected the governments of all persuasions who quite deliberately let the rail system rot.

It was my generation and those who followed who didn’t demand new roads be built as the railways rotted beyond repair and forced us into bigger and bigger trucks.

Now, as the rail rots and the roads crumble before our eyes, we are paying the price for making poor decisions when electing governments. A visitor from the international trucking business told me recently that he didn’t know of any other country in the world that would allow trucks weighing over 120 tonnes to travel on any road, never mind what he called our B Class roads.

We are now paying for our lack of strategic planning with an inefficient, expensive and internationally uncompetitive grain supply chain.

Are we in the same position as America or worse? Should we also be considering our position in the world wheat trade?

Grain yields around the Australia have stalled, why?

I don’t know enough about wheat growing in South Australia and the Eastern States to comment on why their yields have stalled. How do I know they have stalled ? Because a paper written by three CSIRO scientists, which we will come to later, says so.

Professor Kingwell reminded me that the future of wheat growing may not depend totally on what I discussed in my previous article, I agree. He reminded me of the shifting rainfall pattern in WA and the dramatic reduction in sheep numbers as well as increased paddock traffic resulting in hard pans together with herbicide resistance may all have contributed to yield decline. I agree absolutely. All of those possible causes of yield reduction are management issues, even the rainfall decline, if it’s happening plan for it — only plant in the best paddocks — I know some are doing it, but use fallow. The job of management is to observe, consider, measure, predict and act. It not to ignore and pray for a good season.

The wool collapse was in 1990, 27 years ago. That was when the sheep numbers started to decline, coincidentally (perhaps, but I think not) at the same time as yield increases stalled and then in WA, started to decline. The clover-crop rotation took generations and extremely good research and many millions of dollars to develop and was a perfect fit for our soil types. All done when we had an effective Department(s) of Agriculture full of good researchers, experienced extension officers, enthusiastic young men and women graduates who competed for places in the D of A.

All of these people worked alongside the best agricultural research facility in the world in my opinion, the CSIRO. Why the best in the world? Because everything was new, there wasn’t the experience of history and others to fall back on. If that wasn’t enough the D of A in WA had a department devoted solely to getting information from research direct to farmers by Ag Notes and by actively ‘working’ the press. Heady days indeed. We had better extension and communication then than we have now, our reliance on the internet has assumed too much.

Let us not forget the farmers of that time. Thirsting for knowledge and demanding change and at the same time being so innovative that science was often employed to verify what farmers were already doing. So many young farmers pushing the boundaries and demanding the same from others. There was a partnership between science and the paddock — a partnership that drew the plans for what became an agriculture, particularly with merino sheep and tillage systems, that was the envy of the world. Whatever happened?

I don’t know of any research that has been done, which examines the effect on grain yields due to the changes in land management and the inevitable changes inflicted on the soil biosphere caused by the removal of sheep and legumes coupled with the changes in rotation. As for herbicide resistance and hard pans they are a universal problem, which if they are a contributor to declining yields in Australia the question is do they affect others the same way and the answer is I don’t know.

The Wheat Belt NRM has a view but are we listening?

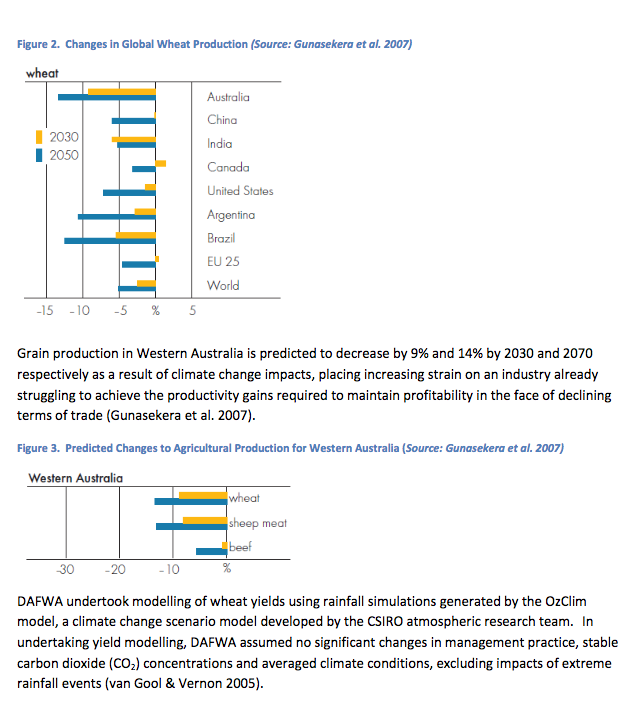

The Wheat Belt NRM has produced a paper Climate Change pdf It is a predictive document based on theirs and others research; they tell us what we can expect to happen to grain yields around the world, in Australia and in WA. It’s an interesting article, it’s not all good news but decision making is not supposed to be easy. It gets easier the more you know. I have reproduced some of their maps and graphs and commend the article to you with the comment that if the predictions are true, the wheat belt of Western Australia is on its way back to range-land farming within the next twenty years. Later on compare what Gunesekara et al are predicting with the opinion of scientists from the CSIRO.

There are other statistics however to gladden the heart of wheat growers. Data collected by Australian Export Grains Innovation Centre (AEGIC) shows that grain growers all around the country are producing more grain with less rain. According to Dr David Stephens. AEGIC agro-meteorologist, Australian grain growers, according to a national study, are up to twice as water efficient as they were 30 years ago,

In an ABC interview Dr Stephens. relates that a comprehensive data map compiled between 1982 and 2012 shows that many wheat growing regions have improved their water use efficiency between 50 and 100 per cent.

Dr Stephens said grain farmers were really “pushing the boundaries” of yield production and water efficiency in terms of adapting to decreasing rainfall.

Dr Stephens. also talks about the efficiency improvements that farmers have made with time of planting and a raft of inputs which have helped them become more water efficient in their crop growing.

An opinion from CSIRO — we are heading for a national average of just 1.55 tonnes per hectare in 2041.

A recent article in ‘The Conversation’ predicts that even if wheat farmers get a lot closer to the ‘potential yield’ than they are today, by 2041 the national average yield will be 1.55 tonnes per hectare, down from where they say it is at present at 1.74 tonnes per hectare.

Yields will never get that low, given that nothing dramatic and unexpected happens like new high yielding drought tolerant wheat varieties, the wheat industry as we know it will be finished long before we get to 1.55 tonnes per hectare, that’s back to the yield of the 70s with the costs of 2041.

The three scientists who make those predictions on yield decline are Zvi Hochman, David L Gobbett and Heidi Horan and they are contained in a recently published article in ‘The Conversation’. It is a comprehensive yet short paper titled ‘Changing climate has stalled Australian wheat yields: study

I recommend the reading of the full article and that you make up your own mind regarding the assumptions made by the authors when they look at the future. Firstly we must get one thing firmly fixed in our minds that is the difference between ‘potential yield’ and what is being achieved or ‘actual yield’. The authors explain; Potential yields are the limit on what a wheat field can produce. This is determined by weather, soil type, the genetic potential of the best adapted wheat varieties and sustainable best practice. Farmers’ actual yields are further restricted by economic considerations, attitude to risk, knowledge and other socio-economic factors.

The authors claim due to worsening weather: ‘While wheat yields have been largely the same over the 26 years from 1990 to 2015, potential yields have declined by 27% since 1990, from 4.4 tonnes per hectare to 3.2 tonnes per hectare.’ Increases in carbon dioxide ameliorated those figures by some 4%, it is claimed.

The authors go on to add: Analysis of the weather data revealed that, on average, the amount of rain falling on growing crops declined by 2.8mm per season, or 28% over 26 years, while maximum daily temperatures increased by an average of 1.05℃.

Overall this means that wheat growers have improved their techniques during that time and they have held yields steady as the potential yield has decreased. The researchers go on to claim, based on weather observations from 50 stations around Australia that the changes in yield have not been uniform across the country. They found that in some areas the potential has not changed whereas in other places yield potential has declined by up to 100 kg/hectare each year, as shown on this map. What about this map? It explains a lot about WA and declining yields and shows how blessed South Australia is:

The research has then looked at how close growers have been able to get their actual yield to the potential yield expressed as a percentage. I have put the words from the original article here in italics because there are interesting links which are well worth following. The authors then ask:

The research has then looked at how close growers have been able to get their actual yield to the potential yield expressed as a percentage. I have put the words from the original article here in italics because there are interesting links which are well worth following. The authors then ask:

Why then have actual yields remained steady when yield potential has declined by 27%? Here it is important to understand the concept of yield gaps, the difference between potential yields and farmers’ actual yields.

An earlier study showed that between 1996 and 2010 Australia’s wheat growers achieved 49% of their yield potential – so there was a 51% “yield gap” between what the fields could potentially produce and what farmers actually harvested.

Averaged out over a number of seasons, Australia’s most productive farmers achieve about 80% of their yield potential. Globally, this is considered to be the ceiling for many crops.

Wheat farmers are closing the yield gap. From harvesting 38% of potential yields in 1990 this increased to 55% by 2015. This is why, despite the decrease in yield potential, actual yields have been stable. (emphasis added)

The article concludes with this horrifying prediction:

Let’s assume that the climate trend observed over the past 26 years continues at the same rate during the next 26 years, and that farmers continue to close the yield gap so that all farmers reach 80% of yield potential.

If this happens, we calculate that the national wheat yield will fall from the recent average of 1.74 tonnes per hectare to 1.55 tonnes per hectare in 2041. Such a future would be challenging for wheat producers, especially in more marginal areas with higher rates of decline in yield potential.

While total wheat production and therefore exports under this scenario will decrease, Australia can continue to contribute to future global food security through its agricultural research and development.

Why 2041? Presumably because they have measured the last 26 years so they extrapolated out for another 26 years? Twenty six years is comfortably a long way off — so far off it that many of us will be driving that big red header in the sky by then and for the rest, thinking ahead 26 years can invoke an emollient response — ‘2041 is a long way away, lets be calm and gentle with our response anything can happen in 26 years.’ ‘Let’s not panic, it’s only a prediction. Yes, yes I know it’s good science but 26 years c’mon!’

To put 26 years into perspective we just have to ask ourselves what were we doing in 1991? Yes it IS that close.

The comforting thing is that in reality we don’t have 26 years, using the figures from this article alone, the wheat industry in most of Australia will be finished long before 2041. In fact, based on the evidence presented here and in my last article, there is a sound, I claim an irrefutable argument that wheat growers in the low yielding areas areas should be planning their exit from the industry starting right now. That is unless they know the fairy with the magic wand.

Stop Press – added 21 Feb

Russian wheat prices rose again last week, thanks to the stronger rouble and African demand.

The Ethiopian government bought about 400,000 tonnes of wheat in a tender, with most expected to be sourced from the Black Sea, following Friday’s Egyptian purchase.

Russian agricultural consultancy IKAR repoted Black Sea Russian wheat ate $191 per tonne at the end of last week, up $3 week on week.

And SovEcon, another Russian consultancy, quoted FOB wheat at $190.5 a tonne at the end of last week, up $1 from a week earlier.

The end.

I make this offer, if anyone disagrees with anything I write then I will faithfully print their opinion, either as a letter or as an article. Providing it stays within our guidelines of editorial standards, it will not be edited. Many thousands read the last article and nobody has disagreed. I have had problems with the email links on this site. To be sure of contacting me use roger.rankin.crook#bigpond.com You know what to substitute the # with. They say it helps to stop scanning, we’ll see.