Australia is part of the Developed World and Australian agriculture has yet to answer the question as to whether it is capable of increasing food production to meet the projected global demands of the future. Are we capable of increasing food production by at least 40% and so help feed the world?

There has to be some doubt whether we can. Terms of trade in agriculture are lousy and our debts are unmanageable. There has been and continues to be, a reduction in both federal and state funds for research and development (R & D) and in a later article we will tell the story behind some frightening figures on the spread of salinity in Western Australia and Australia.

To make matter worse there is a direct correlation between R&D and productivity. There is good evidence that national wheat yields are declining. The national sheep flock is back down to where it was in the 1920s. High slaughtering costs, drought and primitive trade agreements with other countries have pushed both the beef and the live cattle trade from crisis to crisis.

Then there are those in Australia who mischievously, but maybe correctly like to play the fear game and chatter about food security and almost in the same breath raise the spectre of foreigners buying the Australian farm to satisfy their national needs for food in the future. In other words buying Australian farms and exporting produce direct to their own countries, bypassing Australian infrastructure and so denying Australia the chance to trade and so grow.

Recently the Australian agricultural political gossip and xenophobic huffing and puffing has been dominated by opinions of how much of Australia has been bought by Chinese and other foreign investors investors. Rumours have been rife of done deals, broken deals, deals being done and all sorts of people trying to do deals. There is no doubt that there are a lot of Australian farms for sale.

As a friend said to me a few days ago, ‘Most of this Shire is still for sale and we wouldn’t even look at the colour of their skin if they came to buy, all we want to see is the colour of their money, and they can have the lot. One good harvest isn’t going to change anything. Land values have gone down. The bank manager is still there and I’m a year older.’

Australia as the food bowl of Asia.

The climax, the real political orgasm of foreign investment in Australian agriculture was the recent granting to the Chinese of a fifty year lease on 15,200 hectares of Ord Stage 2, to grow, of all things, sugar.

It was the glittering icing, spread thick on the then Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s sponge cake speech promoting Australia as the future ‘Food Bowl of Asia’.

When asked if Ord Stage 2 was an example of the food bowl of the future for Asia, the premier of Western Australia, Colin Barnett, replied with a smile, ‘Sugar is a food.’ Was he genuine or was he being cynical?

Does Colin Barnett understand agriculture? Does he understand that Indonesia already imports fresh produce from Australia for exactly the same reason it wants live cattle, and that is because there is a scarcity of refrigeration in Indonesia that’s going to take a long time to fix.

We have yet to learn the policy of the new federal government on foreign investment in Australia. There appears to be a split in the coalition at the rejection by the Treasurer of the ADM takeover of GrainCorp. What they will do in the future? Nobody knows.

When asked his views on foreign investment, Tony Abbot responded with something like, ‘If we build walls against others they may well build walls against us.’ He also said on election night, ‘Australia is open for business.’ The Treasurer recently repeated that statement. It’s hard to see how when Australian capital funds show no interest in Australian agriculture and we tell the foreigners who do want to invest, to go home.

One thing is for sure, there is another Great Wall of China and this one isn’t built out of bricks and mortar. Chinese farmland isn’t for sale. You can’t buy a Malaysian farm, and no, you can’t buy a farm in Indonesia or Canada. The list goes on so I won’t bore you.

It’s a fair question to ask if the 50-year lease to a Chinese company to develop and grow ‘food’ on the Ord is setting a precedent for the future? The reason that question must be asked is because over more than twenty years our state and federal governments have spent more than half a billion dollars of our money to develop some of the finest irrigation country in the world.

Now, that was our money garnered from our taxes, our governments’ intention at the time, presumably, was to spend our money for our benefit. So where does that leave us now. What kind of return on investment is that to the taxpayers of Australia?

The Chinese will spend another half a billion dollars in developing the land and building a sugar mill.

No doubt local labour will be used to grow and process the sugar. Local carriers will take the sugar to Wyndham, and then it will be loaded on to a Chinese ship, and sold in China. The profit centre will be China, at the retail end of the journey. The cost to grow, it can be argued, becomes almost immaterial.

So that’s it, the most we can expect from our half a billion-dollar investment is a few jobs. Why do I keep thinking about blue gums and how much they cost the local economy when hundreds of thousands of food producing hectares were sold to city investors?

Why are the Chinese coming to Australia to grow sugar?

Answer:Because they are short of land and water in China and sugar needs a lot of water and a lot of fertilizer. Some of the fertilizer, inevitably, finishes up in places other than where it was applied. Just ask Queensland and those who monitor the Great Barrier Reef. China already has more pollution of its waterways than it can manage.

We shouldn’t really be surprised that Ord Stage 2 will be dominated by sugar; many don’t know that vast areas of Ord Stage 1, have been planted to Sandalwood.

Indian sandalwood is estimated to account for about 60 per cent of the total farming area around Kununurra, about 3500 hectares, and has replaced food crops such as melons, pumpkins, legumes, chick peas and bananas.

Queensland Country Life: Ord experiment a ‘failure’ 19 Aug, 2013 08:00 AM

So, the cornerstone of our building a prosperous future to become the ‘Food Bowl for Asia’ is going to be dominated by investment and foreign companies growing sugar and perfume on some of the best tropical irrigation country in the world.

There could be another reason why China wants to grow sugar in Australia. China currently uses some of its precious water to grow vegetables and exports vast quantities of those vegetables to new Zealand, where they get mixed with New Zealand grown vegetables which then get exported to Australia and sold in our supermarkets as ‘Product of new Zealand from local and imported produce.’

Why is China buying wheat-growing land in Australia? Same reason, different crop.

China is the biggest producer of wheat in the world. Wheat yields in China are over 4 tonnes per hectare and are heavily reliant on irrigation. The rate of extraction currently exceeds the rate of recharge. As in many other places in the world the aquifers are slowly going saline as they decline. But China must continue to have sufficient wheat for it’s growing population.

The challenges facing China are enormous. It already has 20% 0f the world’s population and only between 7 and 10% of the world’s arable area.

In recent years the rate of decline in arable land being swallowed up for industry and so housing and all that goes with it is reminiscent of the Industrial Revolution in Britain. The people left the land to work the factories and Britain was forced to repeal the Corn Laws (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corn_Laws) in 1846 and so allow so-called cheap food into the country from North America and the British Empire, including Australia.

The repeal of the Corn Laws laid the foundation for what became Britain’s ever increasing reliance on imported food and brought on a rural recession which lasted, with a couple of minor breaks for World Wars, until the early post war years of WWII and the introduction of what was called the ‘Price Review’.

A system where the government met with the Farmers Union and the ‘prices’ farmers would receive in the following years. ‘Never Again’, was the pledge that Britain would rely on others to feed her. Agricultural subsidies revitalised agriculture and a healthy farm sector poured money into agricultural research from crop agronomy to animal production systems to agricultural chemicals. Britain and then Europe and the United States led the world in innovation and invention, funded by a subsidised agriculture.

It’s not commonly known that Britain was excluded from the EU, mainly by France, until 1973. Britain had to match and in some cases exceed payments made to farmers in what at the time was called the European Economic Community (EEC).

This is from a site developed by the University of Reading in the UK, and shows the dramatic increase in productivity when UK farmers were assured of an income

Since the end of World War II in 1945, British agriculture has become ‘production orientated’. In the second half of the 20th Century farmers were encouraged to maximize yields through the use of increased artificial inputs and improved plant and animal genetics, areas which will be examined in further detail later. This trend continues to the present day, with new technological advances in genetic modification of plants and animals becoming available to farmers. This is demonstrated by the graph below illustrating changes in wheat and barley yields since 1948.

Source: (data) DEFRA, 2011

At the end of the war in 1945, the UK needed to maximize food production. Food rationing did not end until 1953. As a result of this, generous guaranteed prices were continued for major agricultural products. The 1947 Agricultural act was passed (and supported by all political parties) and stated:

The twin pillars upon which the Governments agricultural policy rests are stability and efficiency. The method of providing stability is through guaranteed prices and assured markets.

Annual price reviews were instigated and prices fixed for the main crops (wheat, barley, oats rye, potatoes and sugar beet) for eighteen months ahead. Minimum prices for fatstock, milk and eggs were fixed for between two and four years ahead.

An agricultural expansion plan aimed to raise output from agriculture by 60% over pre-war levels. In 1953, world cereal prices fell and minimum guaranteed prices were replaced by deficiency payments for cereals.

The 1957 agriculture act set out some long term assurances, including:

- Not to reduce the guaranteed price of any product by more than 4% in any one year.

- Not to reduce the price of livestock or livestock products by 9% in total over any three consecutive years.

- Not to reduce the total value of guarantees by more than 2.5% in any one year.

Given stability in prices and guarantee’s, farm incomes rose, giving farmers the confidence to undertake capital investments and utilize the latest technology. This was especially true of arable farming. Cereal prices increased at a quicker rate than other commodities. Crop yields improved due to higher yielding varieties, herbicides and fertilizer. Labour use and costs were reduced as the level of mechanization increased. Increases in incomes on dairy, upland and small farms were slower with less scope for mechanization.

In the 1980s, in spite of her ‘dry’ economic theory and practice, Margaret Thatcher increased agricultural subsidies (as did Reagan in the US) and she saw Britain become first self-sufficient and then a net exporter of food.

It is now accepted that Britain is only about 65% self sufficient in food. Some subsidies have been reduced and the EU says it is committed to continue with the reduction. This may happen, but the EU faces major challenges with an ageing agricultural workforce and in some countries where food growing could not continue without subsidies.

There is now a debate in the EU about achieving a balance between ‘food security’ and reducing the cost of a subsidised agriculture.

The same challenges that faced Britain in the 1800s now face China. A rising population coupled rapid expansion of industry and urbanisation with millions flocking to the city to find work and demanding to be fed.

China’s shrinking arable land.

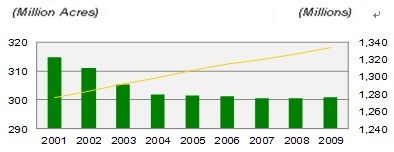

So it’s easy to see from the graph above that China faces some major problems. Just look at the graph, produced by ‘Yongye’. If ever a reason was needed for Chinese expansion into Australia and other countries then there it is.

Yongye say of themselves and of the challenges faced by China: The long-term market growth of crop nutrient products in China is primarily driven by the need to improve crop yield to ensure sufficient food supply in view of limited and shrinking per capita arable land in China. With approximately 10% of the world’s arable land, China needs to feed 1.3 billion people, or 20% of the world’s population. According to the National Population and Family Planning Commission of China, China’s population will reach 1.5 billion by 2030. Therefore, the country faces the challenge of producing additional food to feed the additional 200 million people within the next 20 years. This puts great pressure on China’s agricultural system to increase production output.

It is said by some attention seeking xenophobic politicians, commentators and I suspect frightened and just as xenophobic farmers that we don’t know who owns what land in Australia.

Apparently a register will solve our problems. We don’t want to wake up one morning and find out some foreigner has bought the bloody farm — now do we? Trouble is we already know. At least we know as far as 2011, just a couple of years ago.

The Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), in their publication ‘Foreign investment in Australian Agriculture; published in 2011, estimated that 99% of Australian farming land was owned by Australians.

So the marauding foreigner, in 2010, owned one per cent of Australian farms. According to the World Bank there are 47.2 million hectares of arable land in Australia. So foreign owners owned just 471,000 hectares.

Would you believe that last bastion of the Far Right in agricultural politics and yet at times is seen as being the home of agrarian socialists,Queensland, is the major player in the foreign investment in land stakes? In the RIRDC publication there is this little gem, one can only assume that these land deals were for grazing country and not for arable land:

Foreign landholding in Queensland increased through the first few years of the past decade, declined in the years to June 2004 and 2005 as foreigners sold off their holdings, then increased through the second half of the decade. The most recent data show that around 2.5 per cent of Queensland’s land area is in foreign hands (DERM 2010), of which the United Kingdom accounts for almost half, with the United States, Germany, Netherlands, Switzerland and Hong Kong being other significant landholders.

Then there was this:

The large increase in foreign holdings in 2008–09 was dominated by a single purchase, that of 90 per cent of the Consolidated Pastoral Company by the British private equity company Terra Firma Capital, involving approximately 2.6 million hectares in Queensland. This company purchased a further 600 000 hectares in 2009–10.

So in Queensland at least, it’s the British we really need to watch as they try to buy back the Empire, not the seemingly much feared Middle Kingdom.

Even more curious, Queensland is the home of Warren Truss, Barnaby Joyce and Bob Katter, three of the most vocal critics of the sale of Cubbie Station to a Chinese joint venture, foreign land ownership and who put pressure on Joe Hockey to put the mockers on the GrainCorp deal proposed by the American company ADM.

There wasn’t a murmur from Warren, Barnaby or Bob, which I heard anyway, when British financial invaders bought 3.1 million hectares of their precious Queensland. God Save the Queen?

So compared to Queensland, the 30,000 or 40,000 or even 150,000 hectares, which has reportedly been sold to Chinese interests in the West Australian wheat belt, is to put it mildly, chickenfeed, of little or no consequence in the around 15 million hectares of ‘arable’ land in Western Australia, which is still dominated by what we know as family farming.

Will they make money out of growing wheat in WA, when many have found it difficult for twenty years?

The answer is probably yes. They may well use their own seeding, spraying and harvesting machinery from China, so goodbye John Deere et al.

They may well use their own fertilizer. Their own trucks and we have already been told they will build a facility at Albany port in Western Australia to load their own boats.

So again, the profit centre for their enterprise becomes not the farm gate as it is for the Australian farmer, but the bread shop or bakery or flour mill in China.

It’s called Donald McGauchie’s wet dream, ‘vertical integration’, and it’s as old as the hills and we have never understood it in Australia.

The paradox, the irony if you like, on the other hand, is that Australian owned ‘family farming’, that manifestation, that patriotic affirmation that we are still in control of our own agricultural destiny is really a load of codswallop.

Over the last thirty or forty years, slowly and probably with malice of forethought on behalf of the perpetrators, Australian agriculture has become almost totally reliant on imports. Everything from machinery and chemicals to the majority of fertilizers, are imported.

The average age of farmers is late fifties. In the eastern wheat belt of Western Australia it’s a few years over sixty. We can hold as many forums as we like proclaiming the vigour of our youth in farming and give them a high media profile. We are deluding ourselves; these well-intentioned events become publicity stunts and are mere salves on the wounds of an Australian agriculture without structure.

There are not enough young people in Australia to take over and more importantly, who want to take over the family farm, and the family debt.

What will an expanded foreign ownership do to the social fabric of our ‘wheat belt’? Probably hasten its decline. Already many towns don’t have enough young men to make up a couple of football teams so they import and pay players from the city.

What is most concerning, and for those who don’t want to recognise we have a structural problem in Australian agriculture is to look at how many farms, from the tropics to the south coast, already rely on backpackers and 457 visa holders to get the crop in and off, and man the sidings and receival points at harvest. We do have a structural problem in Australian agriculture.

Without imported inputs, including labour, there would be no Australian agriculture. Whether we like it or not we are totally reliant on others for our living.

The other interesting aspect to this debate was revealed just last year by Matt Paish writing in Australian Food News (AFN). Paish revealed that a report by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences found that foreign firms accounted for about half the nations dairy, sugar and meat processing industries.

To make it all more interesting a report commissioned by the Australian Government’s Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), also says that foreign ownership of agricultural land, business and water entitlements is comparable with the levels of 1983-4.

So, why, what is the motive behind those who have spread a lot of fear and xenophobia about massive increases in foreign ownership of land when in reality nothing much has happened for the last 30 years or so?

Will we all be ‘Rooned’? No. But here are some major structural deficiencies in Australian agriculture, which must be faced up to. Answers must be found.